|

| As the first televised war, the world of the 1960s and 70s could not look away as the violence intensified in Vietnam. The lush paradises of the Vietnamese jungle and countryside turned into a war-torn hell. American B52s were shot down over a freshly bombed Hanoi. Soldiers on both sides returned from the battlefield with trauma, while suffering severe mental and physical wounds. Across the United States, protests erupted, demanding the American government stop killing innocent Vietnamese civilians and drafting young American men to die in a foreign land. One of these antiwar activists was a young medical student named Mark Rapoport. "When I went to college in 1964, the war was the number one political issue in the country," said Mark. "For a person engaged in the world, it was hard not to take a stand." |

|

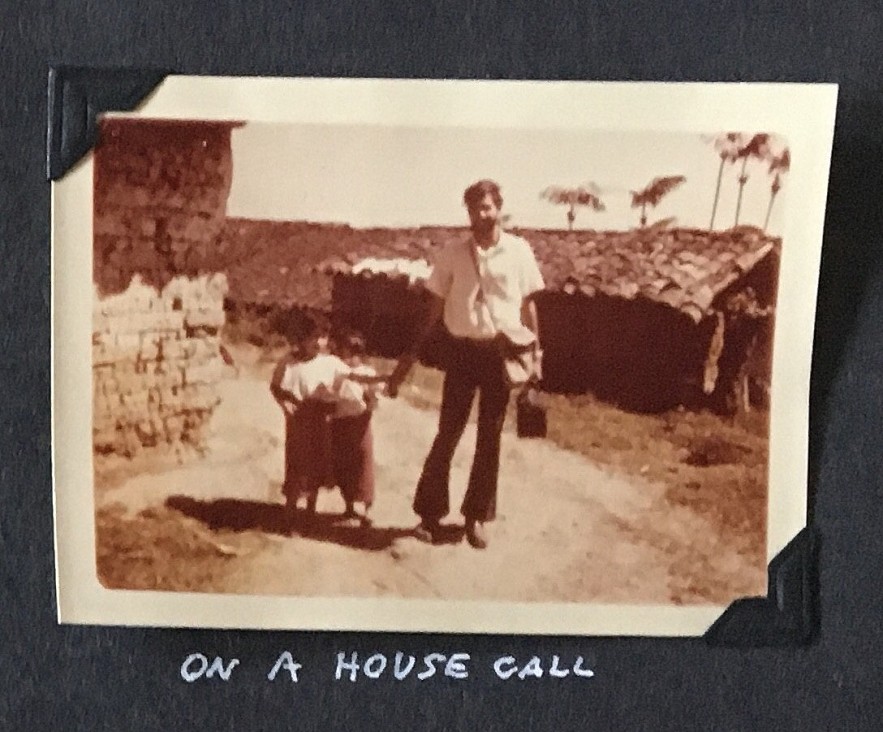

| Mark helped Vietnamese children in 1968. (Photo courtesy of Mark Rapoport) |

| A constant theme in Mark's life is his radical sense of helping those who need it. Coming from a liberal family, Mark was taught compassion for others at a young age. Prior to the war, Mark was involved in a civil rights campaign during his high school years.

Now in his 70s, Mark continues to enhance the lives of Vietnamese civilians, helping the country rebound from war. While a proud New Yorker, he remains critical of the United States's past and present injustices. When asked why he was so adamantly against the war with Vietnam, Mark explains protesting was "intellectually and emotionally mandatory" for him. "Almost everyone that I knew was against the war, most in a deeply personal way," said Mark. "It seemed that demonstrating and the like was necessary, but not at all sufficient to stop the slaughter. The frustration that I and many others felt was intense." Young Americans, particularly students, were very active in the antiwar movement. Many gathered on college campuses to demonstrate their disapproval of the draft and the American military's aggressive tactics. Others argued that a costly war in Southeast Asia drained funds from domestic social programs. The young protestors also demonstrated their support for the Vietnamese people, with signs that read "Vietnam for the Vietnamese" and "DOW Deforms Babies," bringing attention to the deadly chemical, also known as Agent Orange, used by the American forces throughout Vietnam. |

|

| Mark's old photographs of his time in Da Nang. Photo courtesy of Mark Rapoport. |

| Mark was deeply saddened and outraged by the tremendous loss of life caused by the war. "At it's most basic level, it was the killing and maiming of hundreds of thousands of innocent people on the other side of the world for no good reason, by a 'superpower' that really had no business trying to control nations and peoples half a world away," said Mark. "As we learned more about the situation, the degree of immorality became more clear: napalm, white phosphorus, My Lai massacre, Phoenix program--the immorality was endless."

As a supporter of the antiwar movement, Mark signed petitions and attended sit-ins, teach-ins, and intense demonstrations, some of which ended with confrontations with police. As a young medical student, Mark attended these demonstrations as a medic, helping protestors who have been tear-gassed by law enforcement. Wanting to help the Vietnamese people in a more tangible way, Mark volunteered with the American Medical Association and joined a program that addressed the health needs of Vietnamese civilians. In 1968, Mark arrived in Saigon and began working in a Saigonese hospital. A few months later, the medical student was given an opportunity to work in Da Nang, helping set up a tuberculosis vaccination program for a nearby leper colony. "I told them, 'I'm not a real doctor.' They replied, 'We know, but you're the best we got,'" said Mark. At this point, the war was going on for several years and many American military doctors went home or were killed. After arriving in Da Nang, he heard about the health problems of an ethnic community known as the Montagnard in the mountains of Quang Ngai province. Mark knew he had to help them. However, reaching the remote area would not be easy, especially as the jungles were teeming with Vietnamese soldiers. Despite the risks, Mark set off on a mission to help the Montagnard people. Using his ID card that implied he had a higher status than he really did, Mark was able to get access to military medical supplies and convinced American helicopter pilots to fly him the mountain villages. With an interpreter, Mark met with the Montagnard people and began giving them some much-needed medical attention. Before nightfall, the helicopter returned backed to the military base. When asked when he risked his life to save people he never met, Mark thought for a moment before responding with a smile. “I’m sure there are some deep psychological reasons," said Mark with a laugh. "The simple reason is if you're a doctor, you go where people need you.” |

|

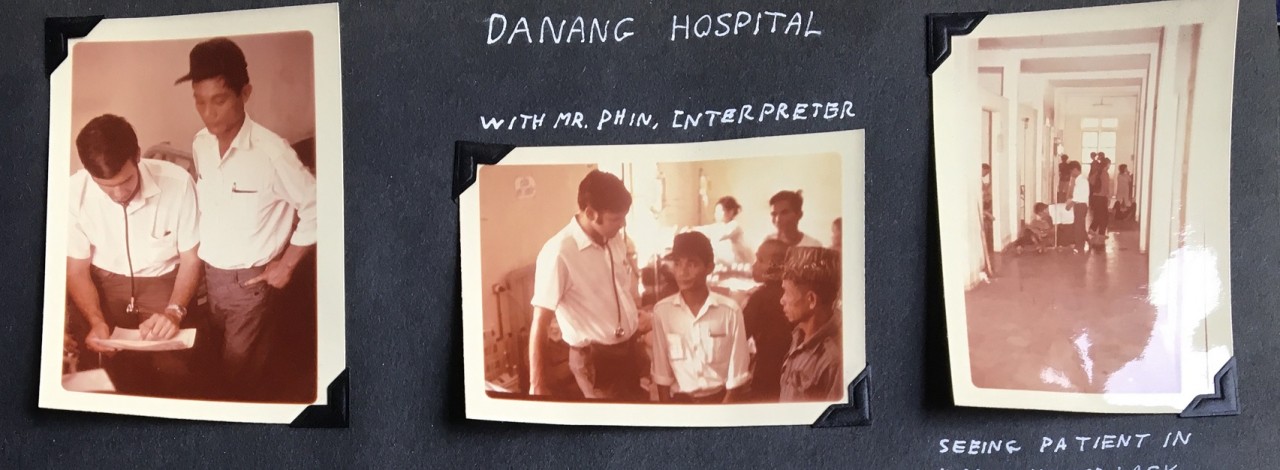

| Mark Rapoport gives glasses to elderly people of ethnic minorities in Vietnam (Photo courtesy of Mark Rapoport) |

| Since leaving Vietnam, Mark continued to administer medical attention to poor communities across the world in places like Nigeria, Guatemala, and in American cities like New York and Boston. Despite the different cultures, Mark continued to witness how poverty exacerbates health issues.

In 2001, Mark and his wife Jane returned to Vietnam, once again using their medical expertise to help the Vietnamese people. Mark assisted in researching Agent Orange while Jane set up AIDs prevention programs. As a lover of anthropology, Mark now collects the pieces made by Vietnam's ethnic communities and donates them to museums in Vietnam and the United States, helping more people understand about the rich culture of Vietnam's ethnic tribes. With Hanoi as their second home, the couple are proud to show their love of the capital city. In fact, Mark, Jane, and their two children published a book entitled 101 Reasons to Love Living in Hanoi in 2010, in celebration of Hanoi's 1,000th anniversary. As a proponent for peace, Mark has reflected on his relationship with the Vietnamese till now. “[During the war] I had debates with myself; if I was in a situation where I had to shoot at a Vietnamese soldier, would I do it?” said Rappoport. “I volunteered to come here, they were doing what I thought was the right thing. No, there was no animosity. They didn’t bomb Boston. We bombed them.” |

| _______________ Writer: Glen MacDonald |