|

| Despite a hostile history, modern Vietnam continues to welcome American tourism and business. Of those returning, many of them are representatives of the US veteran community or military personnel who come to Vietnam to reflect on these atrocities and heal the wounds of war. _____________________ |

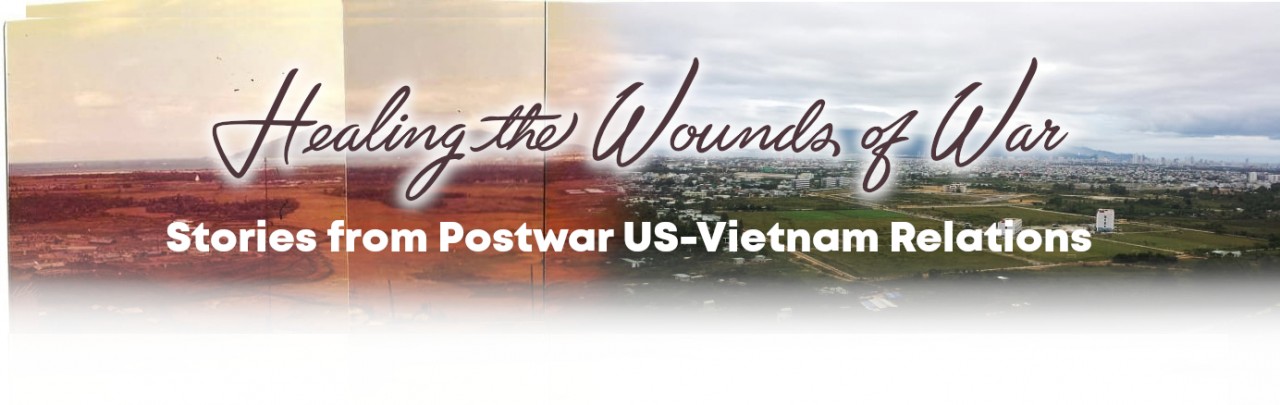

| In February of 2020, as I walked the sunny streets of Da Nang, I heard gruff, American voices among cheerful, Vietnamese chatter. They attempted some passable Vietnamese and ordered more glasses of iced coffee. Gathered under a shady umbrella at the Happy Heart Cafe, a squadron of elderly American men carefully sipped the foreign brew. These men clearly had been in Vietnam for a while as they knew how the coffee here was more powerful than a Stateside ‘cup of joe.’ I also quickly learned to respect the intensity of Vietnamese coffee as I had been in Vietnam for more than a year at this point, working as an ESL teacher. I was born in 1996, a year after Vietnam and the United States normalized relations. While these men grew up watching news reports of war crimes and devastation in Vietnam, I saw Vietnam as a tropical, second home. Many times I wondered how Americans from previous generations would respond when visiting modern Vietnam. I had not spoken to an American elder in ages. Unlike the cantankerous “baby boomers” in my hometown of Bethelhem, Pennsylvania, these men seemed quite pleasant and, like me, happy to explore Vietnam and experience Da Nang’s refreshing sea breeze. I joined them for a bit and we discussed several topics; the upcoming American election, disturbing news from Wuhan, key points around Da Nang to observe the sunrise, the wild habits of monkeys in the Marble Mountains, and where to find the best cheeseburger. Their local knowledge surpassed the average tourist. They spoke about Da Nang with such familiarity as if they had been in Vietnam for generations. We enjoyed our coffees, laughed, and shared stories of our travels. Finally, I asked them a question that was on my mind since I sat down; What was their history in Vietnam? Their answers confirmed my suspicions. They were veterans, long-since retired. Thanks to a settlement with the US military, they were able to relocate to Vietnam and settle down in Da Nang with a majestic view of the Pacific Ocean. “As old men, we wanted to give back to the community we fought against when we were boys,” explained one of the veterans. When not hanging out in cafes, the veterans are still hard at work, assisting local charities, teaching English, or working with victims of war. The previous American empire’s unjustified actions against Vietnam have traumatized thousands on both sides of the conflict. Yet, these American veterans are living proof that Vietnam holds no grudges against their former enemy. After listening to the stories of one-time soldiers becoming agents for peace and reconciliation, I was inspired to hear more from Americans who participated in the war and now have new, uncompromised lives in Vietnam. I wanted to uncover this strange phenomenon; how can returning to a former war zone feel like a friendly homecoming? After speaking with veterans, former military doctors, and Agent Orange victims, I learned about the unfathomable depths of Vietnamese forgiveness. While there is no changing the past, Vietnamese and Americans are forgoing their differences to create a peaceful and prosperous future. |

|

|

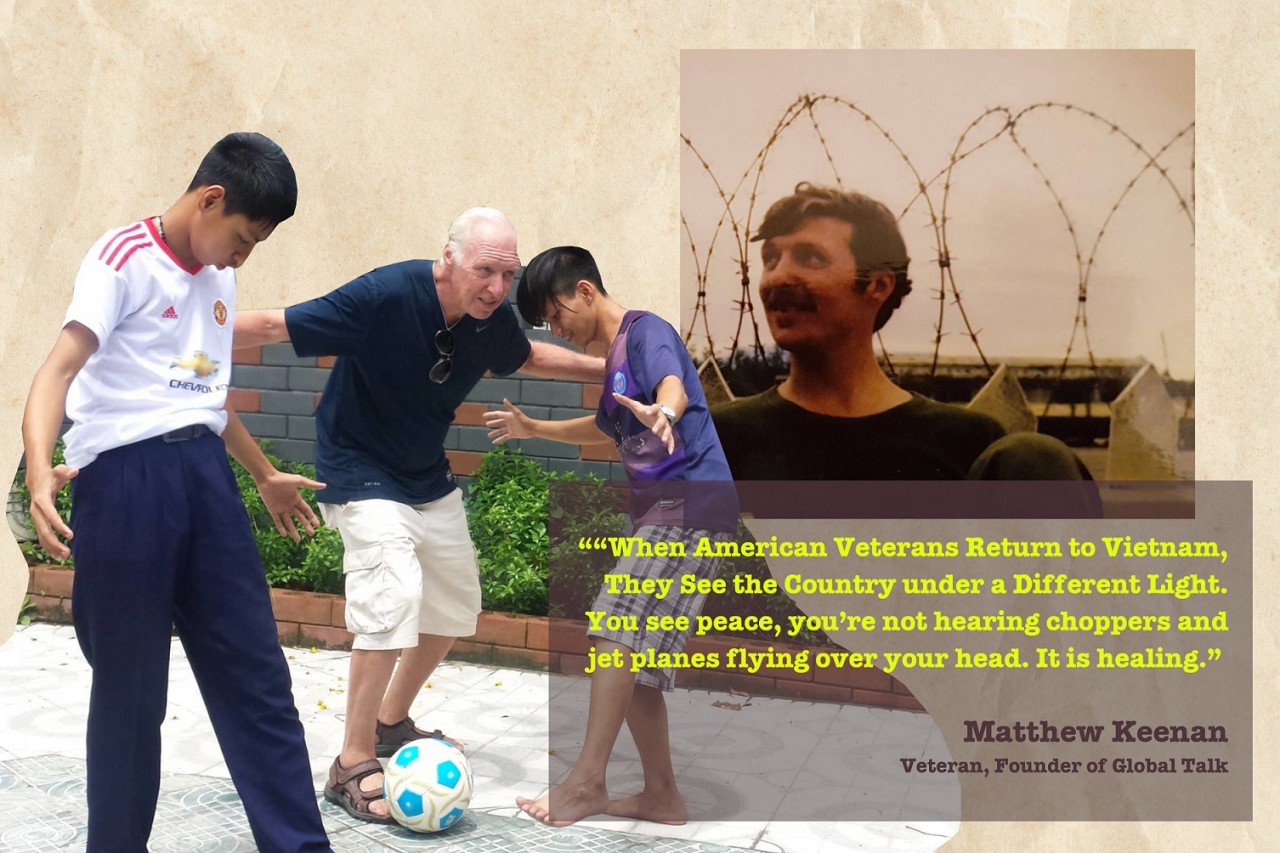

| Following the United States’ bitter defeat in 1973, a war-torn Vietnam struggled under the pressures of American embargoes. During this time, the countries had no diplomatic ties as they both mourned their dead and dealt with their shared trauma. While this was a bleak point in the history of US-Vietnam relations, some dared to believe peace was still possible. According to veteran Charles “Chuck” Searcy, reconciliation between the two nations was “inevitable.” “There were too many people of goodwill who were determined to see the injustices and bitterness of the past replaced by true understanding and friendship,” said Chuck, a fervent supporter of peace between Vietnam and the US. We spoke to each other on a vine-covered Hanoian balcony, a few blocks away from Hoa Lo Prison, where American prisoners of war were once held. Despite the grim location, Chuck remains unfazed as now the prison is a tourist destination where children take selfies by its iconic front doors. As a longstanding expat in Vietnam, Chuck has seen the S-shaped nation change exponentially since first coming to the country as a soldier in 1967, assigned to the 519th Military Intelligence Battalion in Saigon. Through his work in military intelligence, Chuck learned firsthand of the struggles for Vietnamese independence and the brutality unleashed by American orders. Realizing the American people have not been told the truth, Chuck returned to his homeland and vehemently opposed the United States’s immoral actions while joining organizations such as Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW). |

|

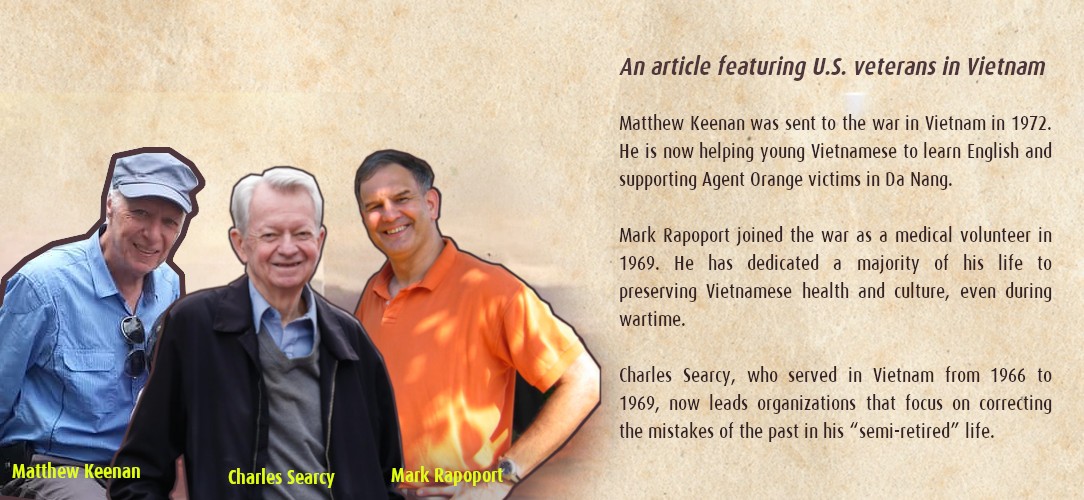

| American veterans were vital in restoring relations between the two countries. Thanks to the influence of John McCain and John Kerry, two American politicians who previously served in Vietnam, President Bill Clinton lifted the trade embargo against Vietnam in 1994 and went on to further normalize relations in the following year. This ushered in a new era of peace and understanding between the two former enemies. Furthermore, it allowed American veterans to return and work in a peaceful, reunified Vietnam. Wanting to make up for the sins of the past, Chuck began work with the Vietnam Veterans in American Foundation (VVAF) to create humanitarian aid projects in Vietnam. Despite the recent diplomatic successes at the time, Chuck admits to being a little apprehensive when he first returned to Vietnam. “When I first came here, I expected I might encounter some hostility,” said Chuck. “I waited, and waited, and nothing happened. I have now been here for twenty-seven years, and no one has uttered a word to me in hostility.”

In his years living amongst Vietnamese people, Chuck has learned a lot from them. Instead of wasting time dwelling on the past, Chuck appreciates how the Vietnamese focus on working for today and bettering themselves for tomorrow. This attitude was key to the postwar rebuilding of their country. Even prior to the country’s economic boom, Chuck reports that the Vietnamese people remained resilient, determined and optimistic, confident that their children would have a better future. “When Vietnamese people talk about the importance of freedom and independence, they mean it,” said Chuck. “It is a genuine expression from the heart. They work to have long-term peace in the world.” Other American expats who participated in the war shared similar stories of acceptance by the Vietnamese people and authorities. After a successful career as doctor in New York City, Mark Rapoport and his wife, Jane, decided to move to Hanoi. Mark, who worked as a volunteer non-military doctor in Da Nang in 1969, developed a special affinity for the Vietnamese people. Despite never being able to master the language, the friendliness of Vietnamese civilians stayed with Mark, even years after the war. “I have visited over seventy countries but only lived in three cities throughout my life; New York, Boston, and Hanoi,” said Mark, dabbing his forehead with a paper napkin. As a Hanoian resident of twenty-one years, Mark is quite familiar with Hanoi’s scorching summers. “I can say in my unhumble, New York, male doctor opinion, there are no better people than the Vietnamese.” In 2001, Mark and Jane planned for their new chapter in Vietnam. However, before fully settling in Vietnam, tragedy struck the USA. Jane was already in Hanoi, working on establishing AIDs prevention programs when she heard the news about a terrorist attack at the World Trade Center. At that time, Mark was still in New York City. While she had no family in Vietnam, she did not have to worry alone. A few hours after the attack, the local authorities and an interpreter arrived at Jane’s office door, offering their support and asking if her husband was alright. Fortunately, Mark was safe and was soon reunited with his beloved wife in Hanoi. While this was an uncertain time for Mark and his family, the gesture by the Vietnamese government reassured Mark that he was safe in Vietnam. “We never felt uncomfortable here,” said Mark. “I love living in Hanoi. Even back then, the streets were alive. The people were welcoming and curious to meet us. While it was a change in living in a different place, the structure of living in a big city didn’t change for me too much.” Since moving to Vietnam, Mark and Jane have made many friends within the nation’s medical community. As any foreigner can tell you, friendships with Vietnamese people makes adjusting to the country so much easier. |

|

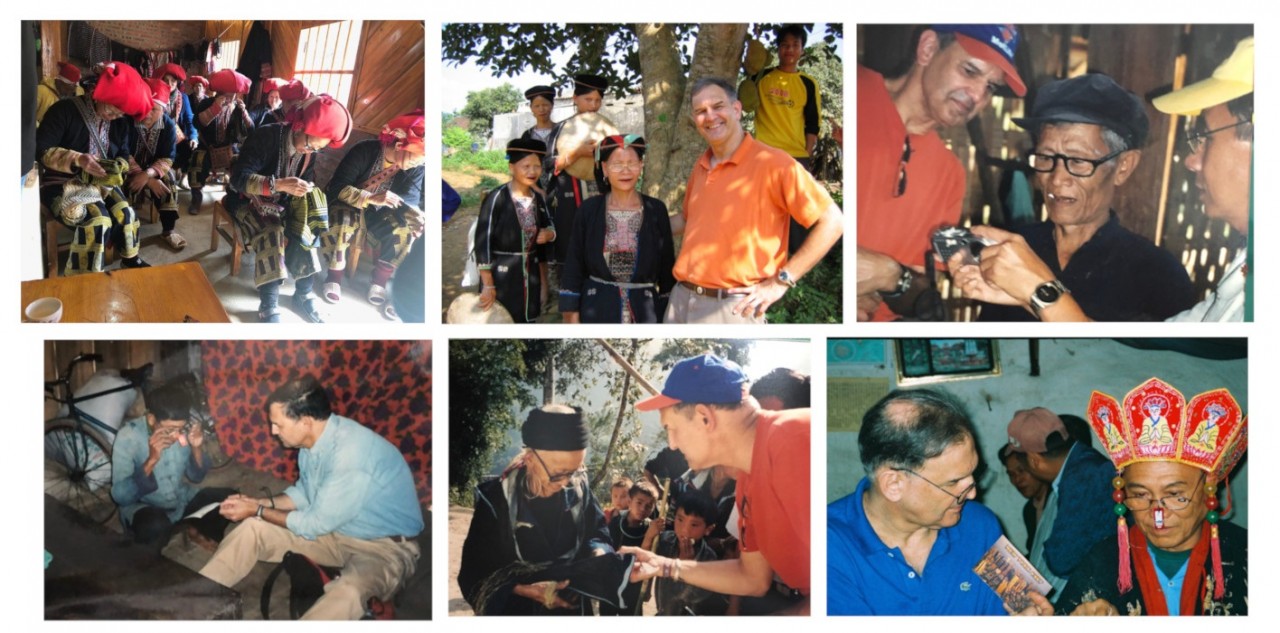

| Mark Rapoport gives free glasses to elderly people of ethnic minorities in Vietnam. |

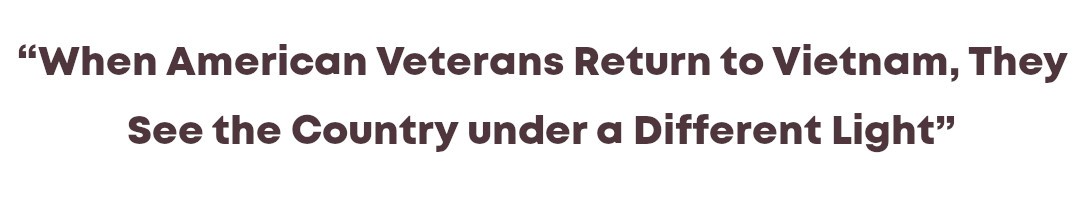

| Arguably, there is no friendship that perfectly encapsulates the postwar relations between US and Vietnam more than Matthew Keenan and Nguyen Ngoc Phuong, an Agent Orange victim who works as a vocational teacher in Da Nang. Matthew and Phuong could not be more different; Matthew is in his seventies while Phuong is in his forties. Matthew has a Doctorate in Law, Phuong has a second-grade education. Matthew towers over Phuong, who is only three feet tall. Despite being a mismatched pair, the two remain close friends and take frequent motorbike rides across Da Nang. While coming from different backgrounds, Matthew and Phuong are united by one of the worst legacies of war; Agent Orange.

It was the death of a childhood friend that inspired Matthew’s postwar pilgrimage to Vietnam. In 2014, Matthew and Jimmy “Beevo” Thompson, who was also stationed in Da Nang, were both diagnosed with cancer, a result of their exposure to Agent Orange. Beevo, who suffered from cancer in his spine, was very sick in the final days of his life. Before his passing, Matthew spoke to Beevo about their shared trauma and disease. “I told Beevo, I don’t want to talk to doctors or other vets. I want to go back to where it happened. I want to go to the people who were directly exposed, where we were directly exposed. I want to go to Vietnam, that’s where it happened.” While still mourning the loss of his friend, Matthew found comfort among his fellow Agent Orange victims. By working with the Da Nang Association of Victims of Agent Orange (DAVA), Matthew began to learn more about the horrendous effects of the dangerous substance while also working to enrich the lives of Vietnamese victims.

Like many others in the central and southern region of Vietnam, Phuong’s father was exposed to Agent Orange during the war and passed on the terrible side effects through his genes. While born with severe birth defects, Phuong continues to make the most out of life and happily works as a vocational teacher. For Matthew, Phuong is an inspiration. “Phuong has limitations and has not let them hold him back. He is extremely resourceful and able to figure out solutions,” said Keenan, when asked about his best friend. “Despite the language barrier we have an uncanny ability to understand each other. He has a great sense of humor, he is loyal and genuine. We have a mutual understanding and bond concerning Agent Orange’s effect on our lives. Phuong's condition is obvious, my condition is internal but our minds are in sync.” Phuong reciprocates Keenan’s kind words; “Agent Orange victims themselves face a lot of physical and mental difficulties, so they need support to relieve the pain that they bear for their whole life. Matthew and American veterans in general, not only in Da Nang but in the whole country, have been really helpful.” Through acceptance by the Vietnamese people, American veterans are able to live happy, peaceful lives in Vietnam. Inspired by the Vietnamese spirit of forgiveness and hospitality, Americans like Chuck, Mark, and Matthew continue to give back to their former enemies, who have now become their close friends. |

|

| When asked why veterans make good advocates for peace, Chuck thinks for a moment before responding. “People show respect to vets by listening to us,” said Chuck. “Lessons learned, opinions, experiences; we share with anyone who listens. In 1975, as Vietnam reunified, I thought at least we learned something from this experience- that most military engagements are unnecessary and that peace requires a lot of work.” Since the conflict began, American veterans and antiwar activists have vocally criticized the harsh foreign policies of the United States. In addition to protests and demonstrations, some have taken it upon themselves to be “people’s ambassadors'' and assist the Vietnamese in rebounding from the years of bombs and bloodshed. As one of those “people’s ambassadors,” Chuck has worked with multiple organizations in the name of Vietnamese-American peace. As the President of Veterans for Peace, Searcy worked to uphold important resources that were crucial to Vietnam’s development such as Hanoi’s Friendship Village, which was founded by another American veteran, George Mizo. |

|

| Like Matthew and Phuong, George Mizo was also affected by the use of Agent Orange. Before succumbing to cancer in 2002 at age 56, George made the Friendship Village as a space for Vietnamese victims of Agent Orange to receive physical therapy, vocational training, and to maintain a cross-cultural dialogue with American victims of Agent Orange. Chuck, Matthew, and other American veterans continue to carry on the legacy of George Mizo by volunteering at the Village, helping children who were born with birth defects. Searcy and Veterans for Peace also worked with Tu Du Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, offering more support for Agent Orange victims. Additionally, his organization helped with storm and flood relief in Quang Tri and Quang Ngai provinces. |

|

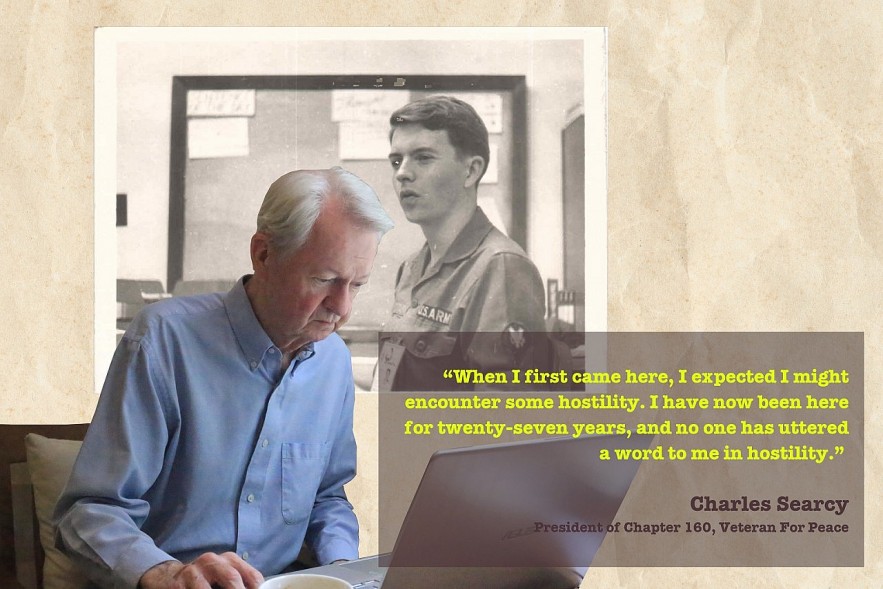

| Chuck Searcy talks to a disabled person with a prosthetic leg at a project funded by project RENEW. |

| Even while “semi-retired,” Chuck is still dedicated to making up for the sins of the past. Currently, he works as an international advisor for Project RENEW, an organization aiming to rid Vietnam of unexploded ordinances (UXOs). In addition to demining, RENEW also provides locals with the knowledge on what to do if they encounter a UXO. Since 2001, the organization has safely removed and destroyed over 105,000 UXOs and cleared 9.3 million square meters for development. While proud of RENEW’s good work, the reason for the organization reminds Chuck of the extreme carelessness dealt by the United States to Vietnam throughout the war. “All of RENEW’s staff members were born after the war,” said Chuck, solemnly. “They take on the responsibility we dumped on them.” |

|

| Bicycle donation for disadvantaged students held by US veterans, including Matthew Keenan, in Quang Ninh in 2021. |

| Deeply invested in the positive development of Vietnam’s younger generation, Chuck, Matthew, and dozens of other American vets living in the country worked together to give away more than 200 bicycles to children from rural, ethnic communities so that they can safely get to school. By giving them bicycles, American veterans are ensuring the next generation of Vietnam is well-educated and ready to take on an ever-changing world. This benevolent project led to another one- GlobalTalk. In order to help raise funds for the bicycle project, Matthew received a generous donation from his former high school, the St. Raymond High School for Boys. After working with educators in Da Nang and New York City, Matthew set up Global Talk, an online forum in which Vietnamese teens can speak to the students of St. Raymond’s. |

|

| Matthew Keenan (left) on his Global Talk project. |

| Beginning last October, this language exchange aims to provide Vietnamese students with the confidence to speak English, while allowing American students to get a better understanding of Vietnamese culture. By connecting his hometown with his second home, Matthew ensures peaceful dialogue continues between the next generation of Vietnam and the United States.

“The American girls were very interested to learn about the Vietnamese ao dai,” said Matthew, referring to Vietnam’s beloved national dress. “They talked about music, dance, and different types of entertainment they liked. Meanwhile, the boys were more interested in sports and video games.” Matthew never imagined he would return to Vietnam in his golden years, much less lead a peaceful dialogue between the next generations of Americans and Vietnamese. “When American veterans return to Vietnam, they see the country in a different light,” said Matthew. “You see peace, you’re not hearing choppers and jet planes flying over your head. It is healing. I never thought I would come back but when I did, I knew I could engage with young and old generations, showing them goodwill.” While entering Vietnam as a medical student rather than a soldier, Mark still feels a uniquely American sense of guilt despite being in a non-combat role during the war. “It seemed to me that there were many kinds of guilt, some worse than others,” explains Mark. “On the one hand, I had never supported the war or supported candidates that did. I felt good about my efforts against the war, so I felt there was some guilt that I did not bear. On the other hand, I (and millions of others), despite our good motives and actions, had been unable to end the killing. Had we been smarter, more dedicated, or more persistent, maybe things would have improved sooner. That very specific guilt fell on all of us in the anti-war movement, and persists to this day.” As a doctor and armchair anthropologist, Mark’s second life in Vietnam was centered around preserving Vietnamese health and culture. Fascinated with Vietnamese ethnic culture, he frequently visits galleries or plans expeditions to trade with local people, eager to learn more about the mysteries of the mountain tribes. He always returns from the villages with many relics, adding to his collection.

Rapoport’s collection boasts dozens of Vietnamese relics but he never intended on hoarding these cultural treasures. Rather, he recently donated 500 pieces to the Vietnam Women’s Museum in hopes that more people can learn about Vietnam’s ethnic minorities. He has also donated a few pieces to American museums, putting Vietnamese art in an international spotlight. “Thus far, Vietnam does not have a tradition of donating things to museums, unlike in the US,” said Mark. “They don’t have an easy way to bring things into the museum to study and display.” Thanks to his generous donation, Rapoport further preserves some of the most remote cultures in Vietnam. During his anthropological trips, Rapoport administers basic medical care for the ethnic communities, continuing his work from 1969. One time, when speaking with an elderly woman in Sapa, Rapoport noticed her squinting while trying to stitch together a shawl. Unable to focus clearly, the woman could not see the fine stitching, hindering her craft. Rapoport gave her his extra pair of reading glasses. Although they were a cheap pair costing no more than a dollar, the glasses were invaluable to the Hmong woman. After seeing how vital these glasses were to the Hmong people, Rapoport knew he had to do more. Then the next time he went to Sapa, he came with a hundred pairs which were quickly taken from him by thankful, withered hands. Afterwards, Rapoport made a protocol named “Reading Glasses for the Mountain Masses,” teaching other tourists and expats about the needs of the Hmong people and how to determine what type of glasses is best for them. In addition to the glasses, Rapoport would also give the Hmong people postcards of the iconic New York skyline. This friendly exchange of culture between Vietnamese and American elders is indicative of how both sides are not intimidated by a hurtful past but rather supportive of a peaceful future. |

|

| Over the years, the leaders of the United States and Vietnam engaged in productive dialogues, summits, and economic agreements for the mutual benefit of both countries. During these meetings, each nation reminisces on how friendship blossomed from the ashes of a painful past. Deaths, blood and tears of previous generations used to be shed to the S-shaped land but today's trust, prosperity and our friendship to be fostered and built up for next juniors and they continue to grow even more deeply in the future. For example, in November of 2000, President Bill Clinton arrived in Hanoi, making him the first U.S. official to visit the Vietnamese capital. He gave a televised speech at the Vietnam National University, stating, “a shared suffering has given our countries a relationship unlike any other” - a sentiment attested by thousands of veterans on both sides of the conflict. |

|

| In 2015, coinciding with the 20th anniversary of US-Vietnam postwar relations, General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong echoed Clinton’s words when speaking at the White House, “In the history of the relations between our two countries, there are sad chapters, but with the spirit of putting aside the past, overcoming differences, promoting similarities, and looking to the future, our countries have built a comprehensive and cooperative relations as seen today.” The postwar relationship is “an inspiring story,” according to Andrew Wells-Dang, a senior expert at the United States Institute for Peace (USIP). Andrew credits individuals like Chuck, Mark, Matthew, and organizations in both countries who took risks to normalize relations between the United States and Vietnam. “There is no guarantee that the two countries that have been enemies will be friends in the future,” said Andrew. “There are not many positive examples in the world.” Through his work with the USIP, Andrew has been involved in several successful dialogues between Vietnamese and Americans, with a mix of government and non-government participants. During these meetings, the international colleagues discuss productive ways to tackle the lasting issues of war such as Agent Orange, demining, and MIA search and recovery. Recently, there were talks about a veterans exchange, bringing the two countries even closer. |

|

| Andrew Wells-Dang, a senior expert at the United States Institute for Peace (USIP). |

| “[During these meetings,] people can’t stop talking,” said Andrew. “There is an eagerness to share those stories and to listen to other stories. And from that, to make sense of what's happened over decades and give meaning to a war that seemed meaningless for many people at the time.” Not just concerned with the past, Vietnamese and American peacemakers also discuss the future. “We are at a transition point,” said Andrew. “The veterans generation, which has contributed many great leaders of the United States and Vietnam, is retired and passing on. There aren’t any more veterans in the United States Congress. Senator Patrick Leahy from Vermont, who has been the greatest champion of supporting war legacies work, is retiring at the end of the year.” Vietnam is also going through similar changes. The younger generation who is replacing older Vietnamese leadership is more familiar with a postwar, friendly United States, giving young Vietnamese a better understanding of American culture and values. However, Andrew wonders how future Vietnamese and American generations will continue to interact, as the war becomes a distant memory. “I often ask myself, ‘can we maintain support for war legacy work?’” said Andrew. “I just visited the Agent Orange cleanup site at the Bien Hoa air base. There is great work being done there but it’s going to take another five to ten years to complete that. The United States needs to continue its commitment to fund that and complete it.” |

|

| Matthew Keenan makes friends with young and old people in Vietnam. |

| While the ghosts of war continue to haunt the battlefields and jungles of Southeast Asia, the world can always look to Vietnam for lessons on forgiveness and peace. Chuck, who has learned a lot from the Vietnamese way of life over his career, came across a profound Vietnamese sentiment, “If the veterans can make peace, why can’t everybody?”

“I am confident that US-Vietnam relations will continue to improve, as we come to realize that our shared history of war has now been transformed into a growing respect for each other and a determination to put peace above all else,” said Chuck. “We need to work together, to talk together as brothers and sisters, and to listen and learn from each other. We still have many mutual benefits that we can experience together.” Chuck’s words echo in my mind as I return to Da Nang, post-pandemic. I find myself once again aimlessly wandering the streets. Late in the day, a swollen sunset illuminates the city in a warm, orange glow. The booming American voices are nowhere to be found. Instead, I hear a playful conversation between young Vietnamese men around my age, sitting by a streetside beer stall. One of them notices me. “Where are you from?” he asks in heavily accented English. “Mỹ!” I respond, in my paltry amount of Vietnamese. My answer prompts several smiles, impressed nods, and beckoning gestures. They offer me a glass of beer and a small, plastic chair next to the fan. I sit with them, apologizing for my terrible Vietnamese skills. It does not seem to matter, as we drink late into the night. While I could only exchange a few sentences with them, it did not impede our laughter. As an American abroad, I consider myself immensely lucky to be here in Vietnam, a proud, ancient nation rebuilt by trusted friends. |

| ___________________ Writer: Glen MacDonald |