|

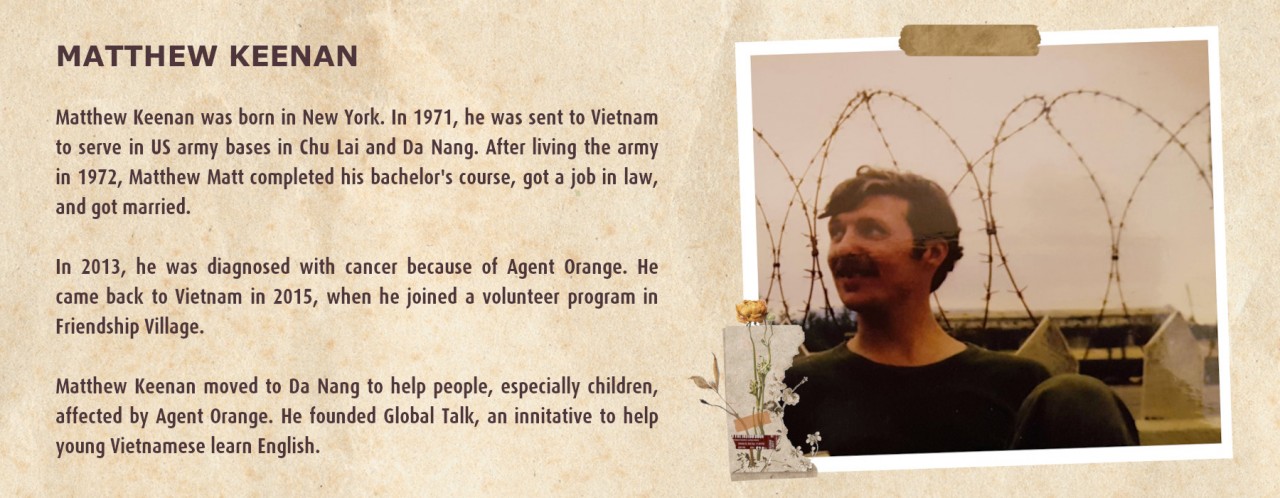

| When and how did you join the war in Vietnam? It was in 1971. I was gonna be drafted but up enlisting. To be honest, I didn’t want to go at all, but I didn’t want to be drafted. Enlisting opened up opportunities for choice.

If I had to go, I wanted to have a say in what I was going to be doing. So that was what happened. I knew I was going to get drafted, so I went enlisting. In the 1970s, the war was going down a bit. For me, it was a gamble. Maybe by the time I got through basic training, the war would be over and I wouldn't have to worry about it. But obviously, that didn't happen. In September 1971, I was sent to Chu Lai and one of my main jobs was to close down the US bases and send personnel back home, then we would transfer the responsibility of the bases to the Vietnamese army. Once we finished in Chu Lai, in November 1971, we went to Da Nang and we started the process in Da Nang. By the time I left Da Nang, Da Nang was just about to be totally turned over to the Vietnamese army. At that time, we may have 20,000 soldiers, and none of them were combated. When you look back at the war, what do you think you reflect on? It was a very difficult time. I felt good about the role I was performing because it was participating in getting the war finished. I was also a drug counselor, helping guys get home drug-free. However, I was always on the fence. There were times when we were doing the right things, then there were times when we were doing the wrong things. The impression in your mind about the conflict, with is known as the “Domino theory," and then you had Muhammad Ali saying what were we doing over there, those people never hurt us.

I can remember one of the hardest times for me was saying goodbye. I remember that every time I say goodbye to somebody, I was happy that I wouldn't have to say goodbye to them again. It was very disturbing because you don’t know if you were going to say hello. My brother was the last person I had to say goodbye to and I was so relieved the goodbyes were over. I didn’t have to worry about it anymore, now I could concentrate on doing my best to get back home, to say hello. When you were in the war, how did you respond to the Vietnamese people? I actually had interaction with a lot of Vietnamese people because the role we played was transferring responsibility to the South Republic Vietnamese army, and there were many Vietnamese women and men who worked at the military bases. They helped clean the hoods, the beds, and our uniforms. I never had any problems with them. Even now, Vietnamese people welcome Americans with open arms. They never say any animosity. I worked with the President of the Da Nang Association for Victims of Agent Orange, Mr. To Nam, who was in Da Nang at the same time I was in 1971 and 1972. He was a courier for North Vietnam. Now we work together as if we were brothers. There is no animosity, we have a good relationship. When he sees me, he salutes me and I salute him back. Now we are on a different mission of reconciliation and forgiveness. We don’t forget about the past but we don’t let that hold us back from doing good deeds. |

|

| When did you hear that you were diagnosed with cancer from agent orange? I had an indication in 2013. My PSA score was high, and that’s one indicator, then I had a biopsy test which came out to show that there was cancer present. So, in 2014, it was confirmed. At the same time, my best friend, who was in Vietnam with me, Jimmy “Beevo” Thompson, was diagnosed. He died. He suffered a great deal. There are at least twenty different medical problems due to Agent Orange. It happened to both the Vietnamese and American people, not only to those who were originally exposed but also to their offspring because it causes genetic problems that pass down to generations. My Vietnamese best friend, Nguyen Ngoc Phuong, 40 years old, is only 95 centimeters tall, because of Agent Orange which he got from his dad, who served the Vietnamese army as a truck driver and was directly exposed. |

|

| Nguyen Ngoc Phuong rides Matthew Keenan on a motorbike specially designed for disabled people. (Photo courtesy of Matthew Keenan) |

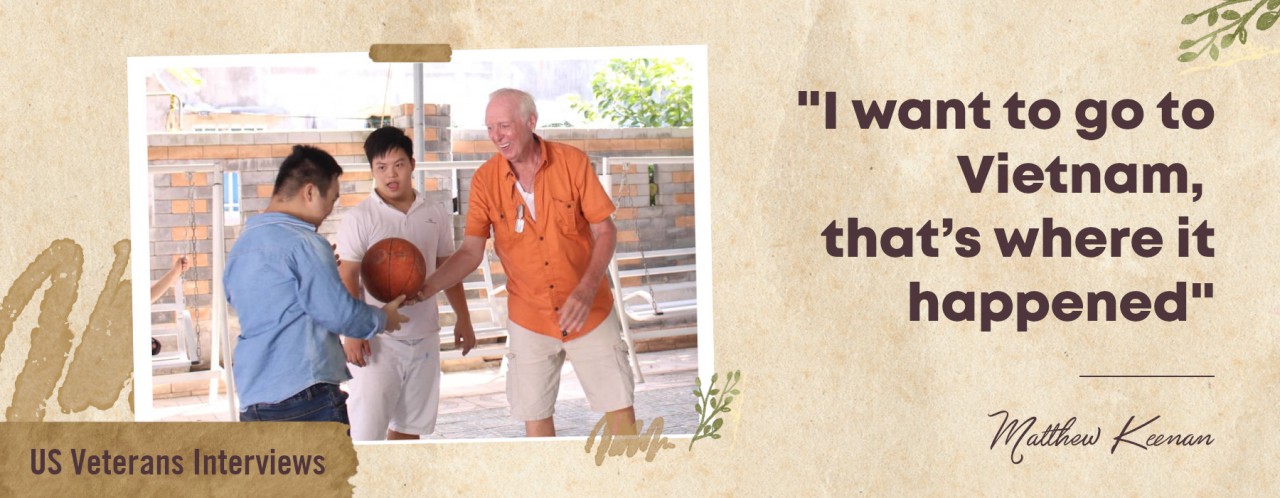

| What made you want to go to Da Nang? At that time, Beevo was very sick and I was diagnosed at the same time. I told Beevo, I didn't want to talk to doctors or other vets. I want to go back to where it happened. I want to go to the people who were directly exposed, where we were directly exposed. I want to go to Vietnam, that’s where it happened. That was my inspiration, I wanted to learn.

It was supposed to be one trip only but after a month, I knew Friendship Village, a boarding school for victims of Agent Orange. My first trip to Vietnam was to Friendship Village in 2015 for a few weeks of volunteering. It was satisfying for me to be engaged to interact with the kids and ministrations. Everything was so nice. Then I said, I was here in Vietnam, I should go to Da Nang, just for nostalgic purposes. I spent three days there and met some people who introduced me to the Da Nang Association for Victims of Agent Orange/Dioxin (DAVA). They took me to one of the daycare centers. I was so interested that when I left Da Nang after three days, I knew I would come back. I made the decision before I left Vietnam that I would go back again. It came to me as an enchanting engagement because it brought joy to me and the kids that I was working with. It was a two-way street. Initially, I just want to engage with the kids in certain activities, to bring them joy. Then after a time, I realized I had a bringer role. These kids didn't know what Agent Orange is, even if you explain to them. My role could be bringing what I was originally doing to a higher level where I can communicate and spread awareness to different areas where we can help funding to help the victims. Can you describe your work with Global Talk? We started last October. The daycare center in Da Nang was closed because of Covid, then the bicycle project came along. Last year, I and my wife were able to give 500 bicycles to the students to get to school. A lot of my friends in New York started to involve and sent money to buy the bicycles. One of the teachers asked me was there anything else we can do as a student body in Bronx, New York to help Vietnamese people. All the time I walked on Da Nang's street, I meet young people who want to speak English. But I think it is better for them to speak with someone of their own age. So I have students here in Vietnam and the high school from which I graduated in New York. It went so well that we added students to the project. |

|

| Matthew Keenan talks about Global Talk. (Photo courtesy of Matthew Keenan) |

| How did you adjust to life in modern Vietnam? I am satisfied not only with my job but also with the people, the environment, and the feeling of safety. In Da Nang I feel safe. I never have to worry about anything. Da Nang is developing. Though geographical locations that remind me of the war are still there, I can see how the people are having a normal life. I appreciate seeing the progress but I can also see places that still need much help. I appreciate the opportunities to work with the future generation. |

|

| _____________ Interview: Glen MacDonald Graphic: Valerie Mai |