Pictures Reveal the Isolated Lives of Japan’s Social Recluses

A photographer explores the hidden world of the hikikomori, and the human bonds that draw them out.

Fuminori Akoa, 29, has been in his room for a year. "According to him, he is a great man and could do extraordinary things, but he does not always try his best," explains photographer Maika Elan who visited him with a social worker. "He changes his hobbies and goals frequently, and says he has gradually become lost."

In Japan, observes photographer Maika Elan, “there are always two sides that oppose one another. It is both modern and traditional, bustling and very lonely. Restaurants and bars are always full, but if you pay close attention, most are packed with customers eating alone. And in the streets, no matter the hour, you find exhausted office employees.”

The counterpart to people living solitary lives in public might well be those who have chosen to shut themselves away. Known as hikikomori, these are people, mainly men, who haven’t participated in society, or shown a desire to do so, for at least a year. They rely instead on their parents to take care of them. In 2016, the Japanese government census put the figure at 540,000 for people aged 15-39. But it could easily be double that number. Since many prefer to stay entirely hidden, they remain uncounted.

Riki Cook, 30, has an American father and a Japanese mother. His family lives mainly in Hawaii while he lives alone in Japan. "Riki always tries to be outstanding," writes Elan, but has a fear of making mistakes.

|

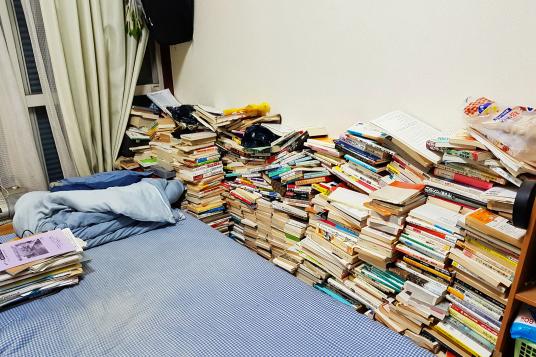

The room of Shoku Uibori, 43, who has been a hikikomori for seven years. "He was a businessman and had his own company but then went bankrupt. He locks himself in the room all day to read and sometimes goes out at night to buy food and other necessities at convenience stores," writes Elan.

At the time when Elan photographed 34 year-old Ikuo Nakamura, he had been in his room for seven years.

Elan, who is Vietnamese, first heard about the hikikomori while she was in Tokyo for a six-month artist residency. She connected with a Japanese woman named Oguri Ayako, who worked with New Start, a non-profit organization centered around drawing the hikikomori out of their seclusion.

At the parents’ request—and at a cost of about $8,000 USD per year—women like Ayako regularly contact the recluse, starting with letters. The process takes months as he goes through the motion of opening them, writing back, chatting on the phone, talking through the door before finally allowing her in. Many more are required before he ventures out with her. The goal is to get him to go live in New Start’s dorm and participate in its job-training program.

Ayako, whose role as a ‘rental sister’ might be best understood as that of a social worker, claims to have helped between forty and fifty of them out of their isolation in her decade-long career.

Elan shadowed Ayako on visits to eleven different hikikomori, and after five or six meetings was allowed to take pictures. “At first, I thought they were lazy and selfish,” she admits, but over time as she got to know them, she learned not only how thoughtful and perceptive they can be. “There are so many people out there working themselves to the ground; the hikikomori, in a way draw Japan into balance.”

'Rental sister' Ayako Oguri writes to Masahiro Koyama, 40, who has been in his room for 10 years. This is Ayako’s third visit to his house. Since he refuses to talk, she writes letters and leaves them in front of his room.

The situation is not unique to Japan, though it is most acute here. Elan cites many reasons why this may be the case: an increasing number of families have only one son in which they put all their hopes and dreams, few of them have male role models since their fathers work day and night, persistent gender roles continue to ascribe much, if not all, the economic responsibilities to the household’s patriarch, to name a few.

Yet another explanation could be found in the country’s cultural shift from a collective-minded society to a more inpidualistic one, especially amongst the younger generations who are seeking ways to express their originality. “In Japan, where uniformity is still prized, and reputations and outward appearances are paramount, rebellion comes in muted forms, like hikikomori,” she says.

“The longer the hikikomori remain apart from society, the more aware they become of their social failure,” explains Elan. “They lose whatever self-esteem and confidence they had, and the prospect of leaving home becomes ever more terrifying. Locking themselves in their room makes them feel ‘safe’.”

Chujo, 24, has been a hikikomori for two years. He has dreams of becoming an opera singer, but as he is the eldest son, his family wants him to join the family business. He worked in an office for a year, but it was so stressful that he suffered from stomach pain. He would also compare his situation to that of his younger brother who could do whatever he pleased. Upset, he would act up, drawing further reprimand from his family, which would, in turn, intensify his feelings of shame. He locked himself in his room for a year before his parents forced him to join a support program.

Elan plans on continuing this project by focusing more on the rental sisters. These women who are strangers to the hikikomori yet may be the solution to their malaise. Case in point, Elan just learned that one of the hikikomori she photographed, Ikuo Nakamura, has since married his rental sister, Oguri Ayako. He now wants to become a rental brother, helping others like him.

The National Geographic

Recommended

Handbook

Handbook

Vietnam Moves Up 8 Places In World Happiness Index

Handbook

Handbook

Travelling Vietnam Through French Artist's Children Book

Multimedia

Multimedia

Vietnamese Turmeric Fish among Best Asian Dishes: TasteAtlas

Handbook

Handbook

From Lost to Found: German Tourist Thanks Vietnamese Police for Returning His Bag

Handbook

Handbook

Prediction and Resolution for the Disasters of Humanity

Handbook

Handbook

16 French Films To Be Shown For Free During Tet Holiday In Vietnam

Handbook

Handbook

Unique Cultural and Religious Activities to Welcome Year of the Snake

Handbook

Handbook