Why the India-US Sonobuoy Co-Production Agreement Matters

|

| the P-8I Neptune - an Indian navy P-81 aircraft. |

In January 2025, India and the United States announced a “first-of-its-kind” defense industrial partnership through the co-production of sonobuoys for use on maritime patrol aircraft like the P-8I Neptune. India’s Bharat Dynamics Limited and the U.S. firm Ultra Maritime signed an agreement the following month to manufacture U.S.-standard sonobuoys in India. This was a critical step in operationalizing deeper defense cooperation between the two countries, particularly in the maritime domain.

Strengthening India’s maritime domain awareness (MDA) has emerged as a central pillar of the India-U.S. security relationship. Complementing initiatives such as the Autonomous Systems Industry Alliance and the Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies, the sonobuoy collaboration reflects a strategic convergence on enhancing underwater domain awareness, a key factor in maintaining a favorable maritime balance of power. As the press release from Ultra Maritime noted, “This first-of-its-kind partnership will enhance undersea domain awareness efforts for both navies.”

The agreement arrives at an important moment. India’s existing shortfall in MDA capabilities severely constrains its ability to conduct anti-submarine warfare (ASW), given that robust undersea surveillance is indispensable for early detection and tracking of adversary submarines. Although India’s naval modernization has focused on expanding seaborne platforms, the inherent limitations of sea-based sensors necessitate strong airborne and space-based support to close surveillance gaps.

India’s induction of U.S.-origin MH-60R Seahawk helicopters, P-8I Neptune maritime patrol aircraft, and the ongoing procurement of MQ-9B Sky Guardian drones aims to bolster airborne maritime surveillance. However, unlike the U.S. Navy’s integration of P-8 aircraft with high-altitude, long-endurance (HALE) MQ-4C Triton drones for broad-area coverage, India currently lacks operational HALE UAVs, with its indigenous Heron and Searcher drones offering limited range and endurance. The MQ-9B acquisition remains pending and will deliver a modest fleet of 15 UAVs for the Indian Navy. All three of these MDA assets can be outfitted with sonobuoys made under the new co-production partnership.

The sheer geographic expanse of the Indo-Pacific demands a scale of surveillance assets far beyond India’s current inventory. With six Seahawks delivered out of the planned 24, 12 operational P-8Is, and a tanker fleet of six aging Il-78s with poor serviceability rates, India needs to step up its capabilities to maintain continuous intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) coverage over the vast Indo-Pacific region. The Pentagon has assessed that India would require 25 to 30 P-8Is to achieve comprehensive maritime surveillance, a number echoed by Indian naval planning documents.

India’s capacity building task list goes beyond airborne surveillance. Expediting domestic manufacturing is an important component in this regard. HAL’s multirole helicopter is not expected until the decade’s end, while the Indian Navy’s requirement for 111 naval utility helicopters under the Strategic Partnership model has also seen some delays. Several frontline anti-submarine warfare corvettes, including INS Kiltan, INS Kamorta, and INS Kadmatt, also require advanced towed array sonars crucial for deep-sea submarine detection.

Space-based maritime surveillance, a potential force multiplier, can be a key asset for Indian surveillance capabilities. India launched phase three of its Space-Based Surveillance (SBS) program in 2024 with plans for 31 strategic satellites. However, at the moment, India lacks dedicated high-resolution military imaging satellites, unlike its robust civilian remote sensing infrastructure.

Even though India’s 2021 initiative to install 42 new coastal radar stations has improved near-shore MDA, vast expanses of the Indian Ocean remain undermonitored. Multilateral efforts such as the Quad’s Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA) initiative are noteworthy but have yet to mature and extend meaningfully into the western Indian Ocean. IPMDA needs to reach out to smaller Indian Ocean states as well, which remain cautious of China’s hegemonic behavior and punitive diplomacy.

In this context, the co-production of sonobuoys represents a force multiplier for India. Sonobuoys enhance ASW operations by enabling rapid, distributed, and persistent underwater detection across vast maritime spaces, bridging gaps left by limited ship and air patrols. Given India’s existing asymmetry in ASW capabilities relative to China’s expanding undersea footprint in the Indian Ocean and the wider Indo-Pacific region – marked by frequent deployments of submarines and dual-use research vessels – bolstering MDA through indigenous sonobuoy production is an urgent operational necessity.

The India-U.S. sonobuoy co-production agreement, while only one piece of a broader maritime strategy, marks an important shift from procurement to partnership and co-development. Sonobuoys can serve as an important component of the much-needed deeper structural reforms India must undertake to achieve holistic MDA: accelerating acquisition cycles, expanding satellite surveillance, investing in unmanned systems, and building a networked ISR architecture that integrates naval, air, space, and cyber capabilities.

With such an integrated approach, India’s impressive fleet acquisitions can effectively deal with overt and covert threats lurking beneath the waves. In essence, the sonobuoy initiative should be seen not as an end in itself, but as an important catalyst toward a more resilient and comprehensive maritime security posture based on the solid foundations of India-U.S. cooperation.

Recommended

World

World

"India has right to defend herself against terror," says German Foreign Minister, endorses Op Sindoor

World

World

‘We stand with India’: Japan, UAE back New Delhi over its global outreach against terror

World

World

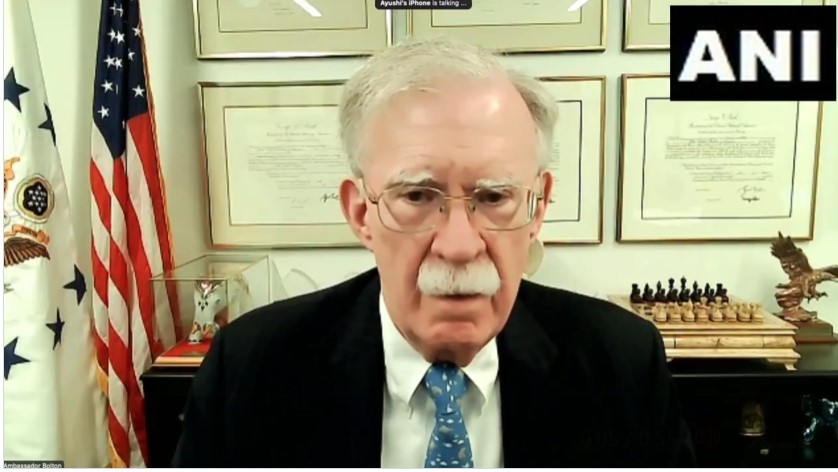

'Action Was Entirely Justifiable': Former US NSA John Bolton Backs India's Right After Pahalgam Attack

World

World

US, China Conclude Trade Talks with Positive Outcome

Popular article

World

World

Nifty, Sensex jumped more than 2% in opening as India-Pakistan tensions ease

World

World

Easing of US-China Tariffs: Markets React Positively, Experts Remain Cautious

World

World

India strikes back at terrorists with Operation Sindoor

World

World