Worshop seeks way for small-scale farmers to regain consumer trust

(VNF) - A workshop discussing how to guarante the quality of safe agricultural products and has the potential to regain consumer trust while improving small-scale farmers' income and natural environment, opened in Hanoi on July 4th.

The event, entitled "Scaling up the trust networks for food safety with small farmers", was hosted by the Belgium Embassy in Vietnam in cooperation with the Hanoi University of Public Health (HUP), International Livestock Research Institute in Vietnam and the Food and Agriculture Oganization of the United Nations (FAO).

The workshop attended by representatives from research institutes and universities, representatives of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Ministry of Health, inter-agencies in the field of food safety, national and international organizations, donors, as well as agriculture producers, retailers and consumers.

| |

At the workshop.

The workshop aimed to provide comprehensive and necessary information on specific identification methods for actors in the food supply chain, thereby enhancing consumers’ trust, providing some directions to build up credible relationships between actors in the supply chain, creating support foundation that enables small scale safety food chains to access the market more efficiently.

The food safety problem

Food safety scandals are run-of-the-mill in Vietnam with more and more new scandal being reported in the newspapers. The chronic overuse of dangerous and low quality pesticides poses a risk for farmers and consumers. The Vietnamese consumer is becoming more and more conscious of this danger, which manifests itself in the rapid increase of the demand for safe, organic vegetables that meet certain standards of safety and hygiene.

All the delegates agreed that recognizing the roles and responsibilities of agents/actors in food safety networks, particularly the role of small-scale production, as well as traceability are important tasks to do in the coming time.

The most disturbing issue for Vietnam lies in the food products consumed domestically, they said, stressing the need to raise public awareness of abiding by laws on producing, processing and providing safe food in addition to enhancing the capabilities of State management agencies on food safety.

Add to that the fact that most Vietnamese farmers are poor smallholder farmers that tend plots of land smaller than one hectare. These smallholder farmers often have a hard time accessing accurate information on how to safely use and store the agricultural chemicals (whether they are allowed or banned) they buy in their local markets. The seller might have given them instructions, but most farmers spray their produce liberally, just to be sure that their harvest won’t be spoiled by a stubborn pest. The result is that a lot of the vegetables that make it to market have unacceptably high levels of chemical residues.

This concern, however, is creating new opportunities for local farmers and civil society to come to together to promote healthy, pesticide-free, sustainable agriculture to meet Hanoi’s growing demand for safe food.

But safe/organic food must be certified as such, and that can become very expensive if smallholder farmers are to adopt the third-party certification system, which requires them to navigate a labyrinth of paperwork and shoulder the cost of an independent auditor to verify compliance with international norms and regulations that often don’t account for many of the challenges of farming in a developing nation. This in turn raises the price of safe/organic produce so much that it became out of reach for many consumers.

The Vietnamese government has implemented VietGAP as the official certification system. Farmers that want to produce VietGAP-certified vegetables go through a thorough process to ensure that their produce comply with VietGAP standards. Part of the process is a costly audit by an external certification company.

In practice, due to its cost and complexity, smallholder farmers are excluded from VietGAP certification. This means that, even if their produce is safe or organic, they cannot sell it as such as they are not certified.

PGS – a community-based certification makes organic food available to all?

PGS (Participatory Guarantee Systems) is a community-based certification system that organizes farmers into groups and coordinates regular peer reviews or inspections of their members.

The groups then come together and connect to consumers, traders, local officials, agronomists and NGOs working in the area. The groups are responsible for making certification decisions, maintaining the PGS standards and procedures, issuing approval seals, assuring compliance with ministry regulations, and publicly promoting the PGS system. Most of the work is conducted on a voluntary basis, which brings down the cost dramatically.

| |

Charlotte Flechet, Monitoring & Evaluation and Communications Officer of VECO Vietnam introduce PGS at the workshop.

To participate in PGS, farmers are required to work in teams, with team leaders responsible for cross-checking products harvested by other farmers and coordinators charged with carrying out regular quality inspections before any certificate to be granted.

PGS guarantees safe and organic vegetables for Vietnamese consumers while improving farmers' income and natural environment, said Charlotte Flechet, Monitoring & Evaluation and Communications Officer of VECO Vietnam at the workshop.

According to her, firstly, PGS is much less expensive than VietGAP, and accessible to small-scale farmers.

Secondly, it entails far less administrative burden. Both of these make it more in line with the reality of smallholder farmers. A third big difference is its approach. As the name suggests, direct participation of farmers and even consumers in the guarantee process is required.

One major advantage of PGS is its certification system. In VietGAP, farmers are audited once by an external company. If they pass the audit they receive their certificate. In PGS, a group of different stakeholders comes together on a regular basis to inspect a farmer’s production process. The stakeholders include government officials, retailers, consumers and other farmers. If the farmer complies with the standards for safe or organic vegetable production, the produce is certified safe or organic and can be sold as such in shops.

Systems similar to PGS have evolved globally, and in 2004 the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) formally endorsed PGS as a viable certification system for organic produce for smallholder farmers.

| |

Q & A session.

In Tu Xa Cooperative, a young cooperative created in December 2015 with the support of Lam Thao district in Phu Tho province, the project adopts the PGS methodology to ensure the quality of safe vegetables for consumers and contribute to securing farmers’ livelihoods and income, said Nguyen Van Nghia, representative of Tu Xa Cooperative.

Delegates ageed that the Government should focus on preventive approach for ensuring food safety rather than on end product testing. They supported the development of PGS as an alternative and complementary tool to third-party certification within the organic sector and advocates for the recognition of PGS by the Government.

They also pointed out that a lot of steps are involved in making PGS work and still more are needed to definitively resolve Vietnam's food safety issues.

Moreover, although motivated to organise themselves as a group and to cultivate safe or organic vegetables, the farmers lacked knowledge on how to apply appropriate farming practices. In some places, local stakeholders’ awareness on safe food and organic vegetable is still low. However, during this event at least some strides were taken in the right direction./.

Chau Pham

Recommended

National

National

Vietnam News Today (May 21): Vietnam Attends UN Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice's 34th Session

National

National

Deep Affection of International Friends

National

National

Vietnam News Today (May 20): Hanoi Named Top Cultural, Artistic Destination in Asia

National

National

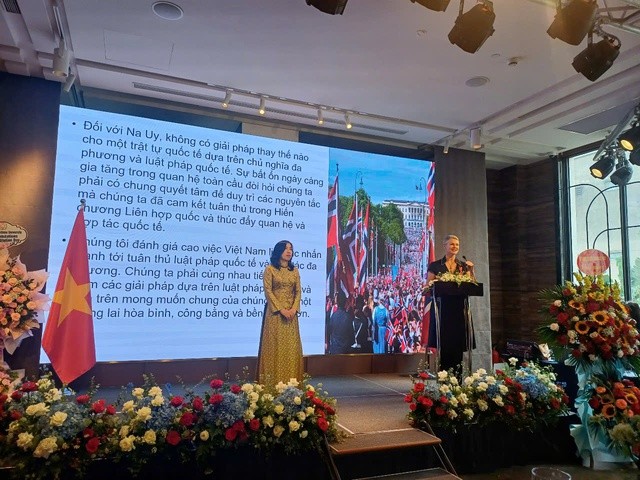

Vietnam News Today (May 19): Norway Hails Vietnam’s Continued Emphasis on Upholding International Law

Popular article

National

National

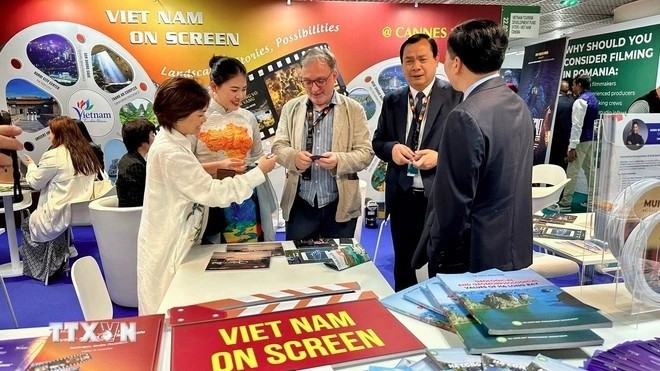

Vietnam News Today (May 18): Cannes 2025: Vietnam Rising as New Destination for International Filmmakers

National

National

Vietnam News Today (May 17): Vietnam and United States Boost Financial Cooperation

National

National

Strengthening Vietnam-Thailand Relations: Toward Greater Substance and Effectiveness

National

National