Delicious Japan: Seven Famous Dishes For a Cool Autumn Time

The days grow cooler in Japan and the foliage turns to red. With the temperatures dropping, the arrival of autumn is something to be celebrated. Autumn is Japan’s traditional season of food and dining. The fall harvest is the best time to enjoy an abundant selection of Japanese ingredients at their peak.

One can enjoy seasonal fish, chestnuts and fruits, all offering sweet fall flavors! Are you ready for autumn's delicious food? Here is the most popular autumn foods in Japan.

1. Momiji Cakes in Miyajima - Maple-leaf shaped desserts on a sacred island

|

| Photo: Flickr |

For sightseeing purposes, Miyajima Island is most famous for its floating Torii, as it is the most well-known and iconic part of Itsukushima shrine. In regards to cuisine and local foods, Miyajima Island is very famous for its "Momiji" flavored, shaped and decorated desserts. "Momiji" translates into maple leaf, and so these local Miyajima desserts are most commonly seen in the very shape of maple leaves, adding to the special and sacred aura of these Miyajima delicacies. Momiji Manju is one of most the popular desserts on the island. Manju is the standard type of wagashi, which are desserts and sweets usually eaten with Japanese tea.

The most common filling for Momiji Manju is azuki bean jam, making the dessert a smooth and delicate texture that melts in the mouth. The dough surrounding the filling - the maple leaf shaped dough - is mildly sweet, and is usually made with the standard wheat flour, eggs, sugar and honey mixture that makes up many Japanese-style cakes. Momiji Manju is perfect for a snacking craving, and is especially aesthetically attractive with its special maple leaf shape.

There are many kinds of manjus, and one of the most famous is matcha tea flavor. The one we are presenting to you today is the momiji manju, a regional variety from Miyajima which has the shape of maple leaves ("momiji") as well as their taste.

2. Shinmai – New rice

|

| Photo: Shutterstock |

Driving through Japan in September and October, you’ll find the landscape a patchwork of golden rice fields, the rice plants dripping with panicles of plump, fawn-colored grains. Their tendrils sway and light green leaves flutter in the breeze; their ripeness fills the air with a sweet, straw-like smell and a sense of anticipation: harvest season for farmers, shinmai (‘shin’ meaning new, ‘mai‘ meaning rice) season for consumers.

Shinmai, officially, is rice that is harvested, processed, and packaged for sale before 31st December of that year. In Okinawa, the season can start as early as July, but in the predominant rice-producing regions of Honshu and Hokkaido, it’s from late August-October.

Shinmai is called so to distinguish it from rice harvested the previous season, as there are characteristic differences: new rice is more sticky, white, and glossy, with 3-20% more water content. To cook, it requires less water; when eating, it’s more plump, moist, and aromatic. Eating shinmai is a treasured and celebrated time in the calendar.

Traditionally, only after the deities had been thanked, and the first taste of new rice experienced by the deities as well as the Emperor, that the less-divine could eat the year’s new rice. These days, the first shinmai tasting by the public doesn’t follow this ritual for various reasons. One is the advancements in harvesting. Rice harvesting used to be much more manual and labor-intensive, taking around a month to sun-dry, and then each grain was hand-picked by hand from the ears of rice – it took around two months from harvesting in September to completing the process in November. Another is the disconnection between the day and its traditional rituals: in 1948, in accordance with the American occupation, General Douglas MacArthur abolished all holidays based on traditional Shinto myths, rituals, and ceremonies, and renamed the occasion Labor Thanksgiving Day.

3. Sanma – Pacific Saury

|

| Photo: Wonderland Japan |

The end of summer brings about the season for the similar-sounding “sanma” – or Pacific Saury. Sanma in Japanese characters, 秋刀魚, means “autumn swordfish”. The aroma of salted, grilled sanma wafting in the air heralds the arrival of autumn and the start of a season loved for its delicious harvests from the land and sea.

Indeed, the southward migration from the northern Pacific Ocean towards Japan at the end of summer is eagerly anticipated by fans who can’t wait to taste what could be Japan’s favorite seasonal fish! Sanma is best raw, of course, to enjoy its freshness and natural oils. However, there are many ways to taste this delicious autumn fish in Japan.

Every September, there’s a Meguro Sanma Festival. The fish is grilled over charcoal and given out to everyone in the line for free! In early Autumn, sanma contains the most oil. In fact almost 20% of its body content is oil. Therefore, the sanma autumn fish makes for a very good grill. Grilled sanma is crispy on the outside and juicy inside.

4. Oden - Warming Soul Food

|

| Photo: Justonecookbook |

Oden (おでん, 御田) is a type of nabemono (Japanese one-pot dishes), consisting of several ingredients such as boiled eggs, daikon, konjac, and processed fishcakes stewed in a light, soy-flavored dashi broth.

Oden was originally what is now commonly called misodengaku or simply dengaku; konjac (konnyaku) or tofu was boiled and eaten with miso. Later, instead of using miso, ingredients were cooked in dashi, and oden became popular. Ingredients vary according to region and between each household. Karashi is often used as a condiment.

Oden is often sold from food carts, though some izakayas and several convenience store chains also serve it, and dedicated oden restaurants exist. Many different varieties are sold, with single-ingredient dishes sometimes as cheap as 100 yen. While it is usually considered a winter food, some carts and restaurants offer oden year-round. Many of these restaurants keep their broth as a master stock, replenishing it as it simmers to let the flavor deepen and develop over many months and years.

5. Yakiimo - Roasted Sweet Potato

|

| Photo: Shutterstock |

On a cool autumn evening or a frigid winter night in most cities in Japan, an ethereal voice can be heard. “Yaaaaaki-Imoooo… Ishiyaki-Imoooo!” (“Baked potato.. Stone-baked potato!). Allow yourself to be lured in by the angelic sounds, and you will soon pick up the scent of something sweet roasting away.

Unlike traditional baked potatoes in the West that do everything to mask the bland flavor of your standard potato, yaki-imo is a call to simplicity, and the beauty it reveals. True to Washoku style, baked potatoes in Japan do not add any butter or spices; they simply throw a washed sweet potato on to some coals and let nature do its work.

There are four types of sweet potatoes that are commonly used for yaki-imo: Satsuma (さつま芋), Annou (安納芋), Milk Sweet (ミルクスイート), and Beni Haruka (紅はるか). Satsuma is the most popular. It provides a starchy punch with a very gentle sweetness, but it is easily overcooked—an overcooked Satsuma potato will leave your mouth drier than the Tottori Sand Dunes.

Of the four, Annou is the stand out for uniqueness of flavor and texture. When cooked right, it will be incredibly tender, practically melting in your mouth, and have a delectable sweetness that’s reminiscent of a good pastry.

6. Kuri - Japanese Chestnuts

|

| Kuri-gohan (chestnut rice) | MAKIKO ITOH |

Fresh chestnuts are one of the few things in Japan that are truly seasonal and not available year-round like so many other food products these days. Chestnuts (kuri in Japanese) have been consumed here since prehistoric times. Charred chestnuts that are more than 9,000 years old have been found in and around the archaeological sites of Jomon Period (10,000-200 B.C.) settlements.

At the 5,500-year-old Sannai-Maruyama site in Aomori Prefecture, evidence of large-scale cultivation of chestnuts has also been discovered — as well as a huge chestnut tree in the center of the settlement that was probably used for religious rituals — indicating their importance as a food source in the days before rice cultivation became widespread. The chestnut wood was valued as building material as well as firewood. Chestnuts are still used in Shinto rituals in some parts of the country, and they’re an important osechi (New Year’s holiday cuisine) dish: a concoction of mashed sweet potatoes with kuri no kanro-ni, chestnuts cooked in sugar syrup. Chestnuts cooked with a crushed gardenia seed are supposed to bring good financial fortune and help make you a winner in life.

Chestnuts are no longer a main staple in the Japanese diet, but they’re still popular in both sweet and savory form. Two of the most popular ways to eat chestnuts these days are imported. One is Tenshin (Tianjin) amaguri, from China, where sweet chestnuts are dry-roasted in a pan and then coated with sesame oil and sugar. The other is Mont Blanc, from France, where pureed chestnut cream and whipped cream is crowned with a sugared chestnut (a proper marron glace or similar). It’s so popular in Japan that it’s far more common here than in France, and there are even faux versions made with pureed sweet potato instead of chestnut cream.

7. Matsutake Mushrooms - Pine Tree Mushroom

|

| Photo: Forager Chef |

Matsutake (Japanese: 松茸), Chinese: 松茸 Tricholoma matsutake, is a highly sought species of choice edible mycorrhizal mushroom that grows in East Asia, Europe, and North America. It is prized in East Asian cuisine for its distinct spicy-aromatic odor.

Matsutake mushrooms grow under trees and are usually concealed under litter on the forest floor, forming a symbiotic relationship with roots of various tree species.

Matsutake mushrooms grow in East Asia, Southeast Asia (Bhutan and Laos), parts of Europe such as Estonia, Finland, Norway, Poland, and Sweden; and along the Pacific coasts of Canada and the United States.

In Korea and Japan, matsutake mushrooms are most commonly associated with Pinus densiflora.

Though simple to harvest, matsutake are hard to find because of their specific growth requirements, the rarity of appropriate forest and terrain and competition from wild animals such as squirrel, rabbits and deer for the once-yearly harvest of mushrooms. Domestic production of matsutake in Japan has also been sharply reduced over the last 50 years due to the pine-killing nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, and the annual harvest of matsutake in Japan is now less than 1,000 tons, with the Japanese mushroom supply largely made up by imports from China, Korea, the Pacific Northwest, British Columbia, and northern Europe. This results in prices in the Japanese market highly dependent on quality, availability, and origin that can range from as high as $1,000 per kilogram for domestically harvested matsutake at the beginning of the season to as low as $4.41 per kilogram ($2 per pound), though the average value for imported matsutake is about $90 per kilogram.

| Thoi Loi: The Weirdest “Tree Climbing Fish” Can Be Found In Vietnam Vietnam is the home to many special and famous specialty of fish, and one of them is called "Thoi Loi" (Giant Mudskipper) that can climb ... |

| Famous Barbecue Dishes and What We Do Not Know Barbecue has been a staple dish not only in America but all around the world, with the methods and styles have been changed to match ... |

| Three Specialties Used to be Seen as Weeds in Southern Vietnam Bulrush, water chestnut and tape grass are three special ingredients in southern Vietnam that used to be considered wild plants. Now, to have a taste ... |

Recommended

Travel

Travel

Vietnam Through Australian Eyes: Land of Flavor, Warmth, and Timeless Charm

Travel

Travel

Strategies for Sustainable Growth of Vietnam’s Tourism from International Markets

Travel

Travel

Vietnam Strengthens Its Presence On The Global Tourism Map

Multimedia

Multimedia

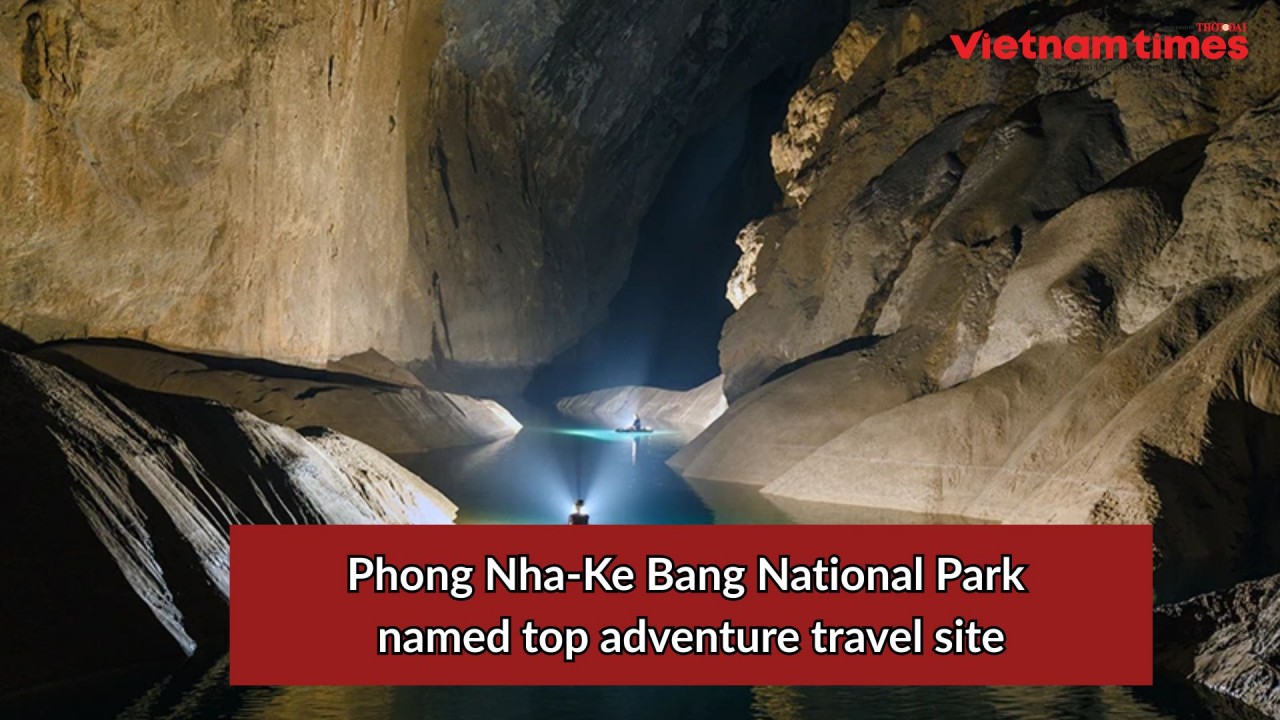

Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park Named Top Adventure Travel Site

Travel

Travel

Vietnam Welcomes Record-High Number of International Visitors

Travel

Travel

Luxury Train From Hanoi To Hai Phong To Be Launched In May

Travel

Travel

Phong Nha Named Top Budget-Friendly Travel Destination for Spring 2025: Agoda

Travel

Travel