Who Is Svante Paabo - Swedish Geneticist Wins Nobel Medicine Prize For Decoding Ancient DNA?

Swedish geneticist Svante Paabo won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine on Monday for discoveries that underpin our understanding of how modern-day people evolved from extinct ancestors at the dawn of human history.

Paabo's work demonstrated practical implications during the COVID-19 pandemic when he found that people infected with the virus who carry a gene variant inherited from Neanderthals are more at risk of severe illness than those who do not, according to Reuters.

|

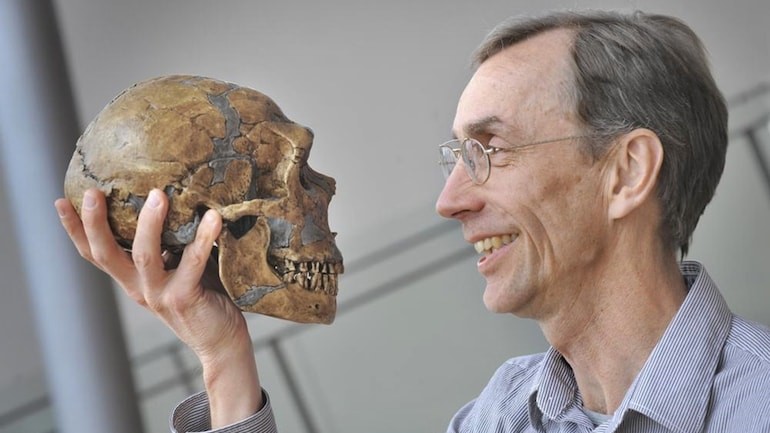

| The Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine was awarded to Swedish scientist Svante Paabo for his discoveries on human evolution. (Photo: AP) |

Paabo, director at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, won the prize for "discoveries concerning the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution," the Award committee said.

"The thing that's amazing to me is that you now have some ability to go back in time and actually follow genetic history and genetic changes over time," Paabo told a news conference at the Max Planck Institute. "It's a possibility to begin to actually look on evolution in real-time if you like."

Paabo, 67, said he thought the call from Sweden was a prank or something to do with his summer house there.

"So I was just gulping down the last cup of tea to go and pick up my daughter at her nanny where she has had an overnight stay," Paabo said in a recording posted on the Nobel website.

"And then I got this call from Sweden and I of course thought it had something to do with our little summer house ... I thought the lawn mower had broken down or something."

Asked if he thought he would get the award, he said: "No, I have received a couple of prizes before but I somehow did not think that this really would qualify for a Nobel Prize."

Paabo, the son of a Nobel Prize-winning biochemist, has been credited with transforming the study of human origins after developing ways to allow for the examination of DNA sequences from archaeological and paleontological remains.

Not only did he help uncover the existence of a previously unknown human species called the Denisovans, from a 40,000-year-old fragment of a finger bone discovered in Siberia, but his crowning achievement is also considered to be the methods developed to allow for the sequencing of an entire Neanderthal genome.

Who is Svante Paabo?

|

| Photo: Wikipedia |

Svante Pääbo (born 20 April 1955) is a Swedish geneticist specializing in the field of evolutionary genetics. As one of the founders of paleogenetics, he has worked extensively on the Neanderthal genome. He is the founding director of the Department of Genetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, since 1997. He is also a professor at Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, Japan.

In 2022, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for his discoveries concerning the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution".

Early Life

|

| Photo: Getty Images |

Pääbo was born in Stockholm and grew up with his mother, Estonian chemist Karin Pääbo. His father was biochemist Sune Bergström, who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Bengt I. Samuelsson and John R. Vane in 1982. Pääbo has via his father one brother, Rurik Reenstierna, who was also born in 1955.

He earned his Ph.D. from Uppsala University in 1986 for research investigating how the E19 protein of adenoviruses modulates the immune system. From 1986–1987, he did postdoctoral research at the Institute for Molecular Biology II, University of Zürich, Switzerland. From 1987–1990, Pääbo was a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Biochemistry, University of California, Berkeley, USA.

Career

Pääbo switched from archeology to medicine, influenced, he says, by his father, the Nobel Prize-winning biochemist Sune Bergström. “At that time, if you were in Sweden and interested in basic biological research, you went to medical school,” says Pääbo. He enjoyed clinical medicine but turned from his medical studies in 1981 to do doctoral research on adenoviruses and their interaction with the immune system. Yet he still had Egyptology on his mind. He wondered if it was possible to obtain DNA from archeological remains. At the time, scientists did not know if DNA could survive intact for a hundred let alone several thousand years. Without telling his Ph.D. advisor (who Pääbo worried might not approve) and with the help of one of his former Egyptology professors, Pääbo obtained tissue samples from a German museum and went to work trying to isolate some DNA from them. His finding— the demonstration that DNA survived in the cell nuclei of some Egyptian mummies—was published in 1984 in a small East German journal, and then again a year later as the cover story in Nature.

|

| Photo: Phys.org |

One of the scientists who read—and was impressed—with Pääbo’s work was the late evolutionary molecular biologist Allan Wilson at the University of California, Berkeley. Wilson had just announced that his lab had isolated a small section of DNA from a zebra-like animal known as a quagga, which had become extinct in the 19th century. Wilson wrote to Pääbo to ask if he could do a sabbatical in Pääbo’s laboratory. “It was before the Internet,” laughs Pääbo. “He had no way of knowing that I didn’t have a lab, that I was just a graduate student.” Pääbo wrote back to explain the situation—and to ask for a postdoctoral position in Wilson’s lab.

Pääbo began working with Wilson in California in 1987. With the aid of the new PCR (polymerase chain reaction) technology, they analyzed mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from a 7,000-year-old human brain. “But we soon came to realize that contamination was a major difficulty,” said Pääbo. The tiniest particle of dust derived from human skin—even from a long-dead museum curator—could ruin the results of their research. Pääbo switched to extracting DNA from non-human ancient creatures, such as mammoths, giant sloths, and the marsupial wolf. That research “helped me work out the techniques and become much more secure in what I was doing,” he says. It also led to some interesting discoveries, such as the finding that moas, the giant flightless birds that were hunted into extinction on New Zealand about 500 years ago, are more closely related to Australian emus than to kiwis, the flightless birds that populate New Zealand today.

Returning to Europe in 1990, Pääbo became a professor of general biology at the University of Munich, where he focused on the development of techniques to study ancient DNA and started applying them to Neandertals, humans’ closest extinct relative “I wanted to learn how the Neandertals are related to people who live today,” says Pääbo. Using specimens from a German museum, he successfully sequenced mtDNA from a Neandertal upper arm bone. That achievement, which was published in the journal Cell in 1997, is considered a watershed in evolutionary genetics. Pääbo’s results had shown not only that DNA could be successfully extracted and sequenced from Neandertal remains, but also that Neandertals and humans were distinctly different groups that split off from each other about 500,000 years ago.

|

| Photo: Japantimes |

In 1997, Pääbo was asked to become director of the Department of Genetics at the new Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, a position he continues to hold today. Over the past decade, he has led the challenging effort to sequence the nuclear genome of the Neandertals. In 2010, he and his colleagues at the Institute published the draft version of that genome, along with the startling finding that Neandertals and modern humans share up to 4 percent of their genetic blueprint.

The finding shows, says Pääbo, that a small number of Neandertals and early humans have interbred. That same year, Pääbo and his colleagues reported a second remarkable finding: A DNA analysis of a finger bone found in 2008 in a Siberian cave showed that the bone belonged to a previously unknown hominin group, which the researchers named Denisovans, after the cave in which the bone had been found. It was the first time a new hominin had been identified by genetic analysis alone. They also showed that Denisovans have contributed DNA to people living in Melanesia today.

Pääbo has also investigated the genetic relationship between humans and great ape populations, particularly how differences in gene expression evolve. “I want to know what happened in the human lineage—in other words, what makes humans special,” he says. Pääbo has identified and studied genes critically important in human evolution, for example, FOXP2, which is associated with language development. In 2008, Pääbo reported that the protein encoded by the FOXP2 gene in Neandertals was identical to that of present-day humans, which raised the tantalizing possibility that they may have had language capabilities similar to present-day humans.

Pääbo has won numerous awards, including the Louis Jeantet Prize for Medicine (Switzerland), the Kistler Prize (USA), and the Leibniz Prize (Germany). He is a member of Sweden’s Royal Academy of Sciences, and in 2004 he became a foreign member of the National Academy of Sciences.

Personal Life

Pääbo lives in Leipzig with his wife, Linda Vigilant, an American primatologist. They have a son, 7, and a newborn daughter.

| Who is the New US Ambassador to Vietnam? Meet Mark Knapper, a decorated career diplomat focused on East and Southeast Asia for decades now being assigned US Ambassador to Vietnam. |

| Who is Teresa Mai, First Vietnamese American Singer Wins Grammy Award Vietnamese-American singer Sangeeta Kaur (Teresa Mai) won the Best Classical Solo Vocal Album at the 2022 Grammy Awards. |

| Who is Vietnamese-American Author Wins the 2022 Best Book Award The recent translation of On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, further cemented Ocean Vuong's connection with his home country. |

Recommended

World

World

Pakistan NCRC report explores emerging child rights issues

World

World

"India has right to defend herself against terror," says German Foreign Minister, endorses Op Sindoor

World

World

‘We stand with India’: Japan, UAE back New Delhi over its global outreach against terror

World

World

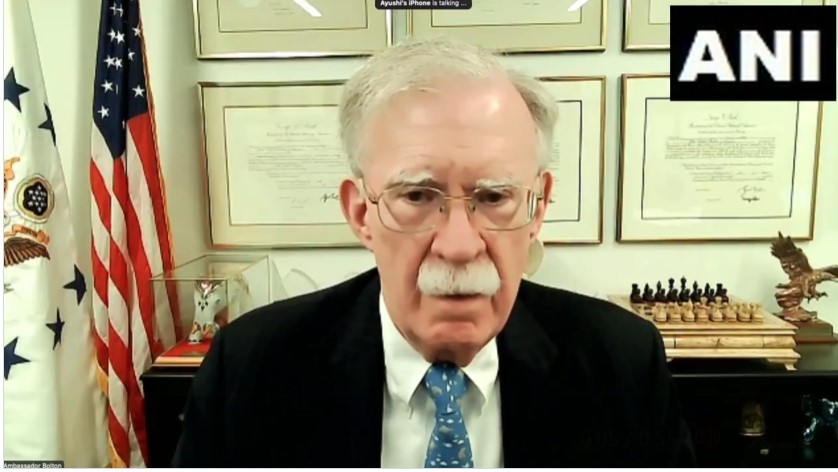

'Action Was Entirely Justifiable': Former US NSA John Bolton Backs India's Right After Pahalgam Attack

Popular article

World

World

US, China Conclude Trade Talks with Positive Outcome

World

World

Nifty, Sensex jumped more than 2% in opening as India-Pakistan tensions ease

World

World

Easing of US-China Tariffs: Markets React Positively, Experts Remain Cautious

World

World