10 Most Delicious and Iconic Italian Dishes To Savor

Fresh, flavorful, and delightfully simple, the sun-kissed Italian cuisine is dolce vita on the plate. But, for finding the best food in a country with such fabulous regional gastronomies, the best advice would be to forget about restaurants that serve “creative, innovative” fare, and just stick to the local, time-honored specialties.

Eating is one of the greatest joys of traveling in Italy, a vivid insight into each region’s culture and traditions. Their dishes are made with seasonal, unpretentious ingredients, yet they taste like something you’d get in a Michelin-starred restaurant.

From regional specialties to the finest seasonal delicacies, you would need multiple lifetimes to sample all the best Italian cuisine, and that’s before you even consider dessert and drinks.

1. Pizza Napoletana (Naples)

|

| Photo: Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana |

Neapolitan pizza, or pizza Napoletana, is a type of pizza that originated in Naples, Italy. This style of pizza is prepared with simple and fresh ingredients: a basic dough, raw tomatoes, fresh mozzarella cheese, fresh basil, and olive oil. No fancy toppings are allowed!

One of its defining characteristics is that there is often more sauce than cheese. This leaves the middle of the pie wet or soggy and not conducive to being served by the slice. Because of this, Neapolitan pizzas are generally pretty small (about 10 to 12 inches), making them closer to the size of a personal pizza.

Neapolitan pizzas are also cooked at very high temperatures (800 F to 900 F) for no more than 90 seconds.

Pizza as we know it today (dough topped with tomatoes and cheese) was invented in Naples. Before the 1700s, flatbreads existed but were never topped with tomatoes, which is now a defining characteristic of pizza.

Tomatoes were brought to Europe in the 16th century by explorers returning from Peru. However, many Europeans believed tomatoes were poisonous until poor peasants in Naples began to top their flatbread with them in the late 18th century. The dish soon became popular. Many visitors to Naples would even seek out the poorer neighborhoods to try this local specialty.

Marinara pizza does not have cheese. It received its name because it was traditionally prepared by “la marinara” (a seaman's wife) for her husband when he returned from fishing trips in the Bay of Naples.

Baker Raffaele Esposito, who worked at the Naples pizzeria “Pietro... e basta così,” is generally credited with creating Margherita pizza. In 1889, King Umberto I and Queen Margherita of Savoy visited Naples. Esposito baked them a pizza named in honor of the queen whose colors mirrored those of the Italian flag: red (tomatoes), white (mozzarella), and green (basil leaves). This is what is now known as the classic Neapolitan pizza today.

2. Bottarga

|

| Photo: Serious Eats |

It goes by many names.

You might know it as karasumi, served along with sake or beer at some izakaya. You might have heard it called eoran if you ate it along with other anju (Korean drinking food), washed down with a swig of soju. Or maybe you call it something else: the Greeks call it avgotaraho; the French, poutarge. In Croatia, they call it butarga, which is closer to the name with which most people in the United States are familiar, if they're familiar with it at all: bottarga. Or perhaps you know it from its name in Arabic, butarkah, from which its Italian name derives.

No matter what you call it, the product is essentially the same: Bottarga is the roe sac of a fish, most commonly grey mullet, which is salted, massaged to expel air pockets, then pressed and dried. It's a delicacy the world over, and it dates back to ancient times. Almost anywhere humans fished, it seems, once they learned of this preservation technique, they extracted fish roe sacs and salted and dried them to produce a deeply savory pantry staple that's resistant to rot. Bottarga is wonderful to eat with vegetables, grated over almost any starch or grain, or just on its own, sliced paper thin and seasoned with a little salt or soy sauce, a squeeze of lemon, and a slick of flavorful oil.

Bottarga and the method for making it was transmitted to civilizations all along the Silk Road, ending up both in the Far East, in places like China, South Korea, and Japan, and in the West, including what is now Italy. It is discussed in Libro de Arte Coquinaria, a book of Italian medieval cookery written around 1465 by Martino de Rossi, who is variously known as "the prince of chefs" or, more dismally, "the world's first celebrity chef." Many of the recipes in the book, which has been translated, outfitted with additional recipes, and published by the University of California Press as The Art of Cooking: The First Modern Cookery Book, were copied entirely by Bartolomeo Sacchi in his gastronomical treatise De honesta voluptate et valetudine, which has the distinction of being the first cookbook ever printed. Of bottarga, the prince of chefs describes the process of making it—use very fresh roe, cure it with salt, press it, then dry—and offers just a small note on how to eat it: "Bottarga is generally eaten raw, but those who wish to cook it can do so by heating it under ashes or on a clean, hot hearth, turning it over until it is hot all the way through."

3. Lasagna (Bologna)

|

| Photo: Delish |

Lasagna is a wide, flat pasta noodle, usually baked in layers in the oven. Like most Italian dishes, its origins are hotly contested, but we can at least say that’s its stronghold is in the region of Emilia-Romagna, where it transformed from a poor man’s food to a rich meal filled with the ragù, or meat sauce.

Traditionally lasagna wasn’t made with tomatoes (remember, those came over from the New World in the 16th century); only ragù, béchamel sauce, and cheese, usually mozzarella or Parmigiano Reggiano or a combination of the two. Even today, only a bit of tomato or tomato sauce is used in a traditional ragu, unlike most Italian-American dishes, which are basically swimming in tomato sauce. This concentrates the flavor of the meat but sometimes is a little jarring for American palates.

Though you can find lasagna throughout all of Italy, there’s nothing like trying the hearty dish in Emilia Romagna with homemade noodles, fresh ragù, and a generous dollop of regional pride

4. Ossobuco alla Milanese (Milan)

|

| Photo: TasteAtlas |

Locally known as l'oss bus a la Milanesa, these wine-braised veal shanks are a classic of northern Italian cuisine and one of Milan's most cherished signature dishes. Ossobuco is believed to have been prepared in local trattorias for centuries, although the first written recipe was found in Pellegrino Artusi's 1891 cooking manual La Scienza in Cucina e l’Arte di Mangiar Bene.

The word ossobuco translates to hollow bone — the cut of veal used for this dish is sliced horizontally through the bone and exposes the marrow, which is what gives the dish its buttery richness. Slow-cooked in beef broth until the meat becomes soft enough to cut with a fork, ossobuco is finished with a topping of gremolà or gremolada, a zesty herb relish made with mashed anchovies, minced garlic, parsley, and lemon zest.

Ossobuco can be served alone or it can be accompanied by polenta, peas, mashed potatoes, or spinach with butter, but for a real feast of flavors, it is best enjoyed with risotto alla Milanese.

5. Gelato (all over Italy)

|

| Photo: EuropeUpClose.com |

Italians haven’t invented the ice cream, but they certainly perfected the process over the centuries. The history of Italian gelato dates back to the Renaissance period, but who exactly created the creamy frozen dessert no one knows.

Most stories on this topic relate that gelato was invented at the court of the Medici, in Florence, either by Florentine architect and designer Bernardo Buontalenti or by the court’s alchemist Cosimo Ruggieri.

Nowadays, there are around 37,000 gelaterie throughout Italy, but some of the best are said to be found in Rome (I Caruso), Florence (La Carraia), and Bologna (La Sorbetteria Castiglione).

Real gelato is made daily by artisans, and, unlike regular ice cream, it contains less fat, less air, and much more natural flavoring. If you want to learn more about the history, culture, and technology of this velvety treat, go visit the Gelato Museum Carpigiani in Anzola dell’Emilia, near Bologna.

6. Panzanella (Tuscany)

|

| Photo: Dishing Out Health |

A staple of Tuscan cuisine, or better yet, Italy’s “cucina povera”, panzanella is a healthy, delicious bread and tomato salad usually served in central Italy during the hot summer months. A classic peasant dish, it has its origins in the green fields of Tuscany, where farmers had to rely on locally grown produce to feed themselves while working.

The region’s love affair with bread salads goes back to the 14th century, but being prior to the discovery of the New World and the introduction of tomatoes in Europe, the original recipe was based on stale bread and onions.

Today’s panzanella, on the other hand, is made with juicy, sun-ripened tomatoes, cucumbers, fresh basil, and leftover bread, and seasoned with olive oil and vinegar.

7. Ribollita

|

| Photo: NYT Cooking - The New York Times |

While on the topic of Tuscany, we would be remiss if we didn’t mention this hearty soup which has become so popular Campbells makes a (not amazing) version. With roots in the peasant cooking of the region, this vegetable soup is thickened with bread instead of meat, because that is what was cheaper and more readily available for hundreds of years in the desperately poor Italian countryside. In Tuscany, the dish is considered a special treat in the autumn, when the taste of the harvest vegetables is at its most vibrant and the soup explodes with an intense savoriness despite the absence of meat (at least in the traditional versions). Often eaten as a first course instead of pasta in the trattorie of Florence, this is one hearty stew that shows off the immense, and often untapped power of great produce.

8. Spaghetti alla Carbonara (Rome)

|

| cookidoo.com.cn |

Carbonara is an Italian pasta dish from Rome made with eggs, hard cheese, cured pork, and black pepper. The dish arrived at its modern form, with its current name, in the middle of the 20th century.

The cheese is usually Pecorino Romano, Parmigiano-Reggiano, or a combination of the two. Spaghetti is the most common pasta, but fettuccine, rigatoni, linguine, or bucatini are also used. Normally guanciale or pancetta are used for the meat component, but lardons of smoked bacon are a common substitute outside Italy.

As with many recipes, the origins of the dish and its name are obscure; however, most sources trace its origin to the region of Lazio.

The dish forms part of a family of dishes involving pasta with bacon, cheese and pepper, one of which is pasta alla gricia. Indeed, it is very similar to pasta cacio e uova, a dish dressed with melted lard and a mixture of eggs and cheese, which is documented as long ago as 1839, and, according to some researchers and older Italians, may have been the pre-Second World War name of carbonara.

There are many theories for the origin of the name carbonara, which is likely more recent than the dish itself. Since the name is derived from carbonaro (the Italian word for 'charcoal burner'), some believe the dish was first made as a hearty meal for Italian charcoal workers. In parts of the United States, this etymology gave rise to the term "coal miner's spaghetti". It has even been suggested that it was created as a tribute to the Carbonari ('charcoalmen') secret society prominent in the early, repressed stages of Italian unification in the early 19th century. It seems more likely that it is an "urban dish" from Rome, perhaps popularized by the restaurant La Carbonara in Rome.

The names pasta alla carbonara and spaghetti alla carbonara are unrecorded before the Second World War; notably, it is absent from Ada Boni's 1930 La Cucina Romana ('Roman cuisine'). The carbonara name is first attested in 1950, when it was described in the Italian newspaper La Stampa as a dish sought by the American officers after the Allied liberation of Rome in 1944. It was described as a "Roman dish" at a time when many Italians were eating eggs and bacon supplied by troops from the United States. In 1954, it was included in Elizabeth David's Italian Food, an English-language cookbook published in Great Britain.

9. Cicchetti (Venice)

|

| Photo: Miranda Loves Travelling |

Cicchetti, also sometimes spelled "cichetti" or called "cicheti" in Venetian language, are small snacks or side dishes, typically served in traditional "bàcari" (cicchetti bars or osterie) in Venice, Italy. Common cicchetti include tiny sandwiches, plates of olives or other vegetables, halved hard boiled eggs, small servings of a combination of one or more of seafood, meat and vegetable ingredients laid on top of a slice of bread or polenta, and very small servings of typical full-course plates. Like Spanish tapas, one can also make a meal of cicchetti by ordering multiple plates. Normally not a part of home cooking, the cicchetti’s importance lies not just in the food itself, but also in how, when and where they are eaten: with fingers and toothpicks, usually standing up, hanging around the counter where they are displayed in numerous bars, osterie and bacari that offer them virtually all day long. Venice's many cicchetti bars are quite active during the day, as Venetians (and tourists) typically eat cicchetti in the late morning, for lunch, or as afternoon snacks. Cicchetti are usually accompanied by a small glass of local white wine, which the locals refer to as an "ombra" (shadow).

One of the most enjoyable aspects of Venetian social life is contained in the phrase: "Let’s go to drink a shadow" (Venetian “Andémo béver un'ombra”). This is an invitation to go for a drink, and more exactly a small glass of wine (a "shadow"), which is typically drunk in one shot. It is a souvenir of the period in which wines were unloaded in the “Riva degli Schiavoni” and then sold in shaded stands located at the base of the Bell Tower of Saint Mark's Cathedral; as the sun changed position, the stands were moved so they could continue to stay in the shade (ombra).

Cicchetti is the plural form. A single piece of cicchetti is a cicchetto.

10. Caponata (Sicily)

|

| Photo: Cooking Light |

Sicilian cuisine is a wonderful mash-up of Greek, Arab, and Spanish influences, but if you only have one meal here, let it be caponata, the island’s beloved eggplant dish.

The star of this warm vegetable salad is the aubergine, but it’s the gorgeous sweet and sour sauce that makes it such an unforgettable vegetarian treat. It usually contains onions, celery, capers, and whatever vegetables people have in their kitchens. Otherwise, there is no standard recipe for caponata, as every house and restaurant has its own version.

For this reason, when eating in Sicily, it is not uncommon to find olives, raisins, pine nuts, and even octopus in your caponata.

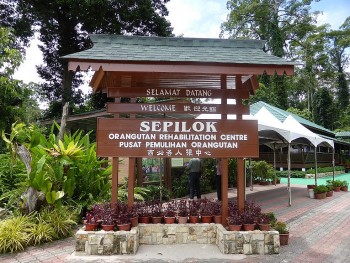

| Explore Top 7 Wonderful and Must-Visit Wildlife Hot-Spots in Southeast Asia From Komodo National Park in Indonesia to Ba Be National Park, these wonderful places have some of the world's most facisnating wildlife that will amaze ... |

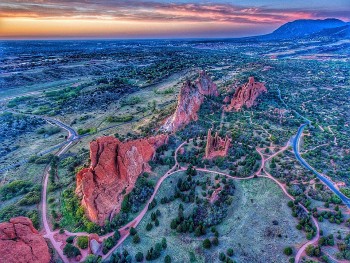

| Step Into The Wilderness: Visit The Mesmerizing “Garden of The Gods” Garden of the Gods, a mesmerizing public park with 300-million-year old sandstone rock formations, is a famous destination in the United States. |

| Visit Mrauk U - The Dreamy Forgotten Heaven of Myanmar As a forgotten heaven, Mrauk U is a hidden ancient city that is nestled in a quite place in Myanmar, where its beauty and mysteries ... |

Recommended

World

World

US, China Conclude Trade Talks with Positive Outcome

World

World

Nifty, Sensex jumped more than 2% in opening as India-Pakistan tensions ease

World

World

Easing of US-China Tariffs: Markets React Positively, Experts Remain Cautious

World

World

India strikes back at terrorists with Operation Sindoor

Popular article

World

World

India sending Holy Relics of Lord Buddha to Vietnam a special gesture, has generated tremendous spiritual faith: Kiren Rijiju

World

World

Why the India-US Sonobuoy Co-Production Agreement Matters

World

World

Vietnam’s 50-year Reunification Celebration Garners Argentine Press’s Attention

World

World