The Secrets Of Colossi of Memnon – The Unearthly “Singing” Statues

The Colossi of Memnon are two enormous statues of 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Amenhotep III originally designed to guard his mortuary temple, located on the western bank of the Nile, opposite Luxor.

The Colossi of Memnon, also known as Colossus of Memnon, are two massive stone statues on the west bank of the River Nile, opposite the modern city of Luxor, in Egypt. The statues are incredibly tall, about 18 meters high. They represent Pharaoh Amenhotep III, who reigned ancient Egypt some 3,400 years ago.

The history of Colossi of Memnon

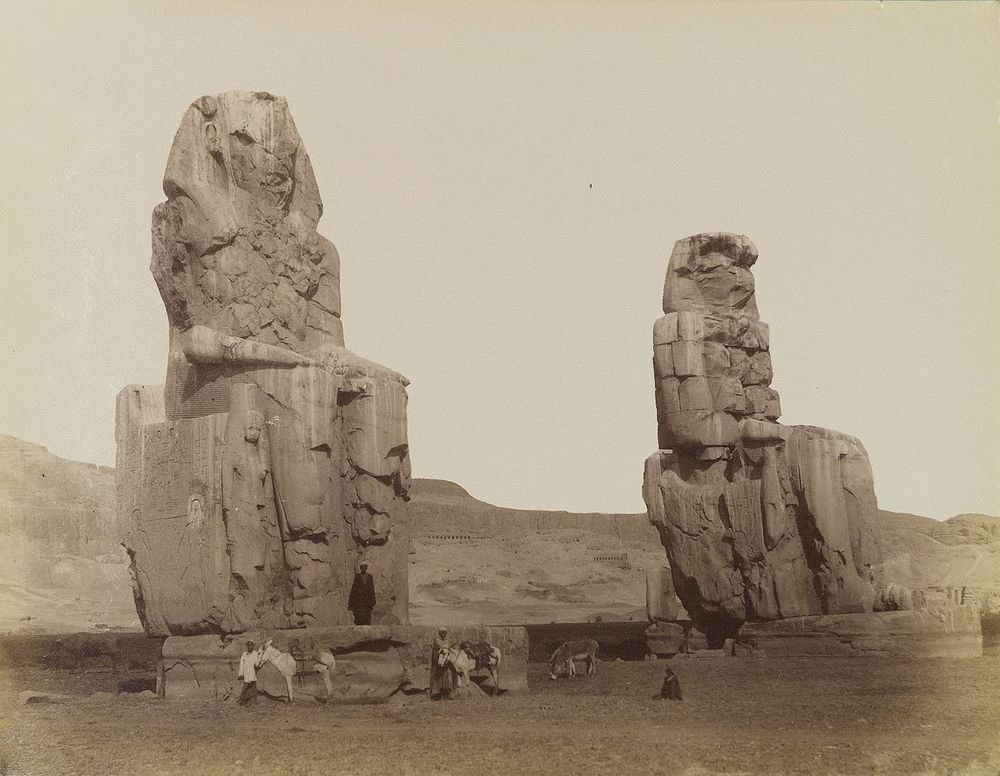

|

| The Colossi of Memnon, battered by time and accidental Roman damage. ARSTY / DESPOSITPHOTOS.COM |

Memnon was a hero of the Trojan War, a King of Ethiopia, who led his armies to Troy's defense but was ultimately slain by Achilles. Memnon was said to be the son of Eos, the goddess of dawn, and after his death, his mother is said to have shed tears —or dew drops— every morning. The “singing” of the statues was attributed to his mother mourning for her son, or perhaps, Memnon singing to his mother? Many early visitors didn’t even know they were statues of a long-dead pharaoh. They thought the statues were of Memnon.

The twin colossi (which no longer resemble twins) depict the Pharaoh Amenhotep III, who ruled during the 18th Dynasty. They once flanked the entrance to his lost mortuary temple, which at its height was the most lavish temple in all of Egypt. Their faded side panels depict Hapy, god of the nearby Nile.

|

| The statues. MARC RYCKAERT (CC BY 3.0) |

Through centuries of floods reduced the temple to no more than looted ruins, these statues have withstood any disaster nature throws their way. In 27 B.C., an earthquake shattered the northern colossus, collapsing its top and cracking its lower half. But strangely, the damaged statue did more than merely survive the catastrophe: After the earthquake, it also found its voice.

At dawn, when the first ray of desert sun spilled over the baked horizon, the shattered statue would sing. Its tune was more powerful than pleasant; a fleeting, otherworldly song that evoked mysterious thoughts of the divine. By 20 BC, esteemed tourists from around the Greco-Roman world were trekking across the desert to witness the sunrise acoustic spectacle. Scholars including the likes of Pausanias, Publius, and Strabo recounted tales of the statue’s strange sound ringing through the morning air. Some say it resembled striking brass, while others compared it to the snap of a breaking lyre string.

The unearthly song is how these ancient Egyptian statues wound up with a name borrowed from ancient Greece. According to Greek mythology, Memnon, a mortal son of Eos, the goddess of Dawn, was slain by Achilles. Supposedly, the eerie wail echoing from the cracked colossus’ chasm was him crying to his mother each morning. (Modern scientists believe early morning heat caused dew trapped within the statue’s crack to evaporate, creating a series of vibrations that echoed through the thin desert air.)

|

| A 19th century photograph of the Colossi of Memnon. Photo credit: Antonio Beato/Wikimedia |

Sadly, well-intentioned Romans silenced the song in the third century. After visiting the storied statues and failing to hear their ephemeral sounds, Emperor Septimius Severus, reportedly attempting to gain favor with the oracular monument, had the fractured statue repaired. His reconstructions, in addition to disfiguring the statue so the fixtures no longer looked like identical twins, robbed the colossus of its famous voice and rendered its song a lost acoustic wonder of the ancient world, according to Atlas Obscura.

The legends of “Singing” statues

The earliest report in literature is that of the Greek historian and geographer Strabo, who claimed to have heard the sound during a visit in 20 BCE, by which time it apparently was already well-known. The description varied; Strabo said it sounded "like a blow", Pausanias compared it to "the string of a lyre" breaking, but it also was described as the striking of brass or whistling. Other ancient sources include Pliny (not from personal experience, but he collected other reports), Pausanias, Tacitus, Philostratus, and Juvenal. In addition, the base of the statue is inscribed with about 90 surviving inscriptions of contemporary tourists reporting whether they had heard the sound or not.

|

| Two shorter figures are carved into the front throne alongside his legs: these are his wife Tiy and mother Mutemwiya. Photo credit: Ben Tubby/Flickr |

The legend of the "Vocal Memnon", the luck that hearing it was reputed to bring, and the reputation of the statue's oracular powers became known outside of Egypt, and a constant stream of visitors, including several Roman emperors, came to marvel at the statues. The last recorded reliable mention of the sound dates from 196. Sometime later in the Roman era, the upper tiers of sandstone were added (the original remains of the top half have never been found); the date of this reconstruction is unknown, but local tradition places it circa 199 and attributes it to the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus in an attempt to curry favor with the oracle (it is known that he visited the statue, but did not hear the sound).

Various explanations have been offered for the phenomenon; these are of two types: natural or man-made. Strabo himself apparently was too far away to be able to determine its nature: he reported that he could not determine if it came from the pedestal, the shattered upper area, or "the people standing around at the base". If natural, the sound was probably caused by rising temperatures and the evaporation of dew inside the porous rock.

|

| Photo: Kasadoo |

Similar sounds, although much rarer, have been heard from some of the other Egyptian monuments (Karnak is the usual location for more modern reports). Perhaps the most convincing argument against it being the result of human agents is that it did cease, probably due to the added weight of the reconstructed upper tiers.

A few mentions of the sound in the early modern era (late 18th and early 19th centuries) seem to be hoaxes, either by the writers or perhaps by locals perpetuating the phenomenon.

Visiting the Colossi

The Colossi of Memnon are usually included on guided tours of the ancient Thebes necropolises of the Valleys of the Kings and Queens, and the Temple of Hatshepsut.

| The Most Perfect Winter Weekend Getaways in the U.S November is the holiday season, with many fun and holidays around the United States, and families spend time with each other celebrating Thanksgiving, or gathering ... |

| Utah - The Land With The Most Beautiful Natural Wonders In The United States Utah, the land of desert, sunny days, rocky mountains, and hills, is the perfect destination for people who are looking for adventures and wilderness. |

| Discover Beautiful Nepal In The Autumn Time November is a perfect time to visit Nepal, one of the most attractive destinations in the world. Thousands of people come here each year to ... |

Recommended

World

World

India reports 9 Pakistani Aircraft Destroyed In Operation Sindoor Strikes

World

World

Thailand Positions Itself As a Global Wellness Destination

World

World

Indonesia Accelerates Procedures to Join OECD

World

World

South Korea elects Lee Jae-myung president

Popular article

World

World

22nd Shangri-La Dialogue: Japan, Philippines boost defence cooperation

World

World

Pakistan NCRC report explores emerging child rights issues

World

World

"India has right to defend herself against terror," says German Foreign Minister, endorses Op Sindoor

World

World