Covid-19 in India: Warnings of virus mutations that can "evade immune response"

However the advisers said while they were flagging the mutations, there was no reason currently to believe they were expanding or could be dangerous.

Scientists are studying what led to the current surge in cases in India and particularly whether a variant first detected in the country, called B.1.617, is to blame. The World Health Organization has not declared the Indian variant a “variant of concern,” as it has done for variants first detected in Britain, Brazil and South Africa. But the WHO said on April 27 that its early modelling, based on genome sequencing, suggested that B.1.617 had a higher growth rate than other variants circulating in India, according to Reuters.

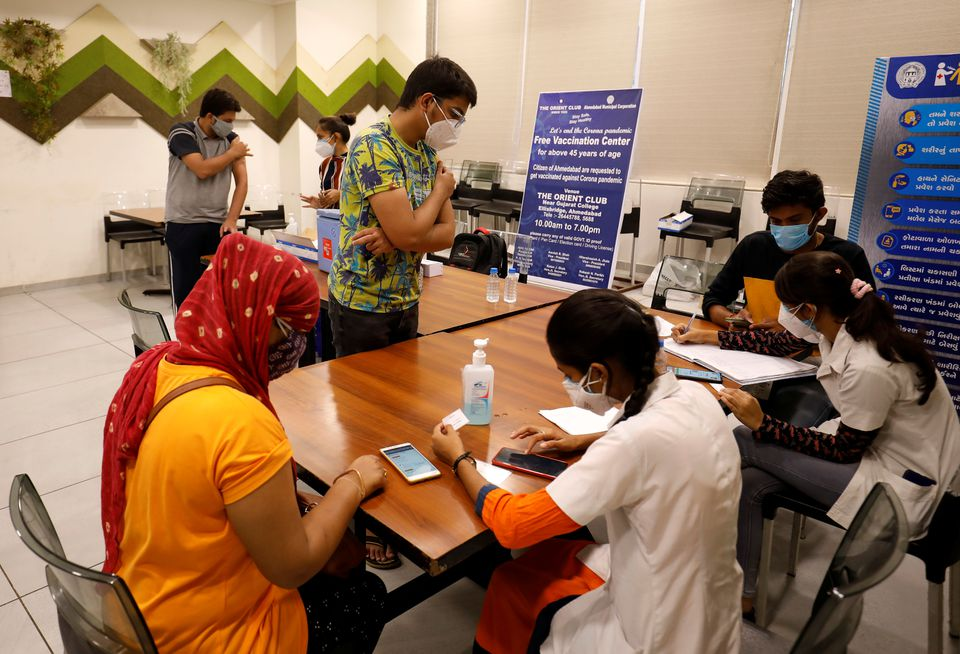

|

| People get their names registered after receiving a dose of COVISHIELD, a coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccine manufactured by Serum Institute of India, at a vaccination centre in Ahmedabad, India, May 1, 2021. REUTERS/Amit Dave |

The forum of advisers, known as the Indian SARS-CoV-2 Genetics Consortium, or INSACOG, has now found more mutations in the coronavirus that it thinks need to be tracked closely.

"We are seeing some mutation coming up in some samples that could possibly evade immune responses," said Shahid Jameel, chair of the scientific advisory group of INSACOG and a top Indian virologist. He did not say if the mutations have been seen in the Indian variant or any other strain.

"Unless you culture those viruses and test them in the lab, you can't say for sure. At this point, there is no reason to believe that they are expanding or if they can be dangerous, but we flagged it so that we keep our eye on the ball," he said.

INSACOG brings together 10 national research laboratories.

India reported more than 400,000 new COVID-19 cases for the first time on Saturday. The rampaging infections have collapsed its health system in places including capital New Delhi, with shortages of medical oxygen and hospital beds.

'Double mutant' variant is adding fuel to India's COVID-19 crisis

|

| Photo: Reuters |

A deadly second wave of coronavirus infections is devastating India, leaving millions of people infected and putting stress on the country’s already overtaxed health care system.

Officially, by the end of April, more than 17.9 million infections had been confirmed and more than 200,000 people were dead, but experts said the actual figures were likely much higher. In the same period, India was responsible for more than half of the world’s daily Covid-19 cases, setting a record-breaking pace of more than 300,000 a day, New York Times reported.

Months ago, India appeared to be weathering the pandemic. After a harsh initial lockdown, the country did not see an explosion in new cases and deaths comparable to those in other countries.

But after the early restrictions were lifted, many Indians stopped taking precautions. Large gatherings, including political rallies and religious festivals, resumed and drew millions of people.

Beginning this spring, the country recorded an exponential jump in cases and deaths.

Alarmed by the local outbreaks of B.1.1.7, the variant first discovered in the United Kingdom, the government formed a multi-laboratory network named the Indian SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Consortium (INSACOG) to monitor the evolution of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. On March 24, after sequencing less than one percent of coronavirus samples collected by its member laboratories across the country, INSACOG announced it had found “a new double mutant variant.” What alarmed scientists was that the variant carried features from two worrisome lineages; the variants first identified in California (B.1.427 and B.1.429), and those discovered in South Africa (B.1.351) and Brazil (P.1).

A variant emerges

Although it wasn’t noticed at the time, the mutant had in fact been sequenced and its genetic code deposited in the global database as early as in October 2020, but “it seemed like it just wasn't on anybody's radar screen,” says David Montefiori, who studies viral immunology and vaccine development at Duke Human Vaccine Institute. This new variant has spread fast, causing more than 60 percent of all coronavirus infections in the Indian state of Maharashtra alone, which reported the largest number of all COVID-19 cases in India.

|

| A makeshift Covid-19 care facility in Delhi in late April.Credit...Atul Loke for The New York Times |

The emergence of more transmissible variants highlights major limitations in the current state of global surveillance of not only SARS-CoV-2 but of all emerging diseases in far-flung areas. INSACOG was expected to sequence five percent of the positive samples from all states but managed far fewer: only 13,614 by April 15. “This is a global problem,” says Montefiori.

“Certainly, the world has lots and lots of genomic surveillance, and I feel very strongly that India needs to be doing a much higher proportion. Often people ask how much? The U.K. is the gold standard on genomic surveillance and maybe between five and 10 percent. India does far less than one percent,” says Dr. Ashish Jha, a public health policy expert at the Brown University.

What is a “double mutant”?

Viruses frequently mutate and these mutations occur randomly, says So Nakagawa of Tokai University who has been studying the variants first discovered in California. In fact, SARS-CoV-2, HIV, and influenza viruses, all of which encode their genetic instructions using the molecule RNA, mutate more frequently than other types of viruses due to copying errors introduced as viruses replicate in their host cells, according to National Geographic.

More than a million distinct sequences of SARS-CoV-2 have been reported to GISAID, the global public database. Many inconsequential mutations go unnoticed. But some mutations can change the amino acids, which are the building blocks of viral proteins, “which may change their characteristic,” Nakagawa says. When one or more mutations persist, instead of being evolutionarily cast off, they create new variants distinct from the ones already in circulation and are then given new names.

The new variant, now designated as B.1.617, carries two known mutations; the first at position 452 of the spike protein and the second at 484. “[But it] shouldn't be called double mutation, because that is just a misnomer,” says Mishra.

Actually, B.1.617 carries 11 other mutations—13 in total, of which seven are in the spike protein that punctuate the surface of SARS-CoV-2 and endow the virus with its signature “crown” structure. The virus uses spike proteins to anchor to the ACE2 receptor protein on the surface of lung and other human cells, and infect them. An eighth mutation in B.1.617 located at the midpoint of the immature spike protein—and also found in some New York variants—can increase the transmission of the virus, giving it an adaptive advantage.

“The mutations in the B.1.617 have been studied independently, but not in combination,” explained virologist Benjamin Pinsky. “What's important …there's a lot of mutations coming up in the spike protein.”

| India pledges to protect overseas Vietnamese during second Covid-19 wave Indian Ambassador to Vietnam affirmed that New Delhi will do its utmost to support and protect Vietnamese Indians against the complicated pandemic that is devastating ... |

| Indian COVID-19 Updates (April 29): Indians rush for vaccines as death tops 200,000 The last 24 hours brought 360,960 new cases for the world’s largest single-day total, taking India’s tally of infections to nearly 18 million. It was ... |

| Vietnamese in India fearful amidst Covid-19 storm Vietnamese in India, the world’s current Covid-19 epicenter, are fearful of the country's drastic spike in new cases of the coronavirus |

Recommended

World

World

Pakistan NCRC report explores emerging child rights issues

World

World

"India has right to defend herself against terror," says German Foreign Minister, endorses Op Sindoor

World

World

‘We stand with India’: Japan, UAE back New Delhi over its global outreach against terror

World

World

'Action Was Entirely Justifiable': Former US NSA John Bolton Backs India's Right After Pahalgam Attack

World

World

US, China Conclude Trade Talks with Positive Outcome

World

World

Nifty, Sensex jumped more than 2% in opening as India-Pakistan tensions ease

World

World

Easing of US-China Tariffs: Markets React Positively, Experts Remain Cautious

World

World