Southeast Asia's Successful (and Unsuccessful) COVID-19 Responses under professor's views

| Millions of Southease Asian jobs might sufffer as COVID-19 goes rampant | |

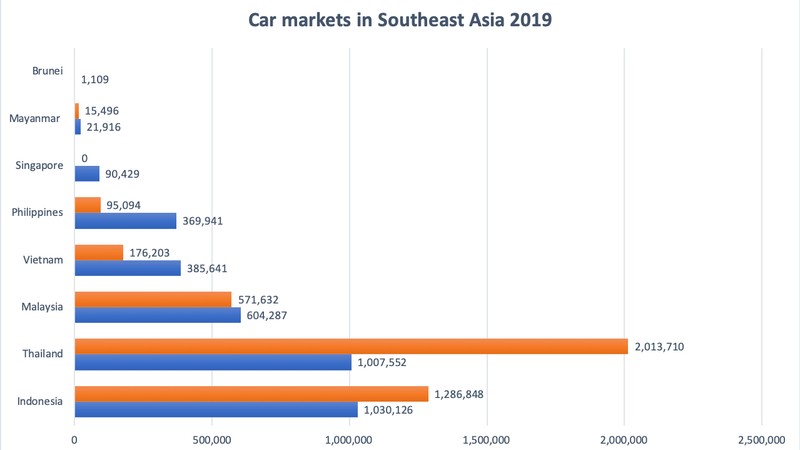

| Vietnam car market ranks fourth in Southeast Asia | |

| Vietnam the third most active tech ecosystem in Southeast Asia |

|

| Thediplomat reported on Covid-19 response in The South East of Asia |

The Diplomat is an international online news magazine covering politics, society, and culture in the Asia-Pacific region. It is based in Washington, D.C. In December 2010, the online news aggregator RealClearWorld (R.C.W.) cited The Diplomat as one of the top-five world news sites of 2010. In 2011, RCW again listed The Diplomat as one of its top-five world news sites

By April 21 2020, The Diplomat reported an analysis written by Zachary Abuza, a professor at the National War College in Washington, D.C on the response to COVID-19 across Southeast Asia, indeed around the world which saw varied. Professor Abuza said that: We have seen huge disparities in the number of confirmed cases, even when we account for cases per capita. There are enormous differences in case fatality rates, from well under 1 percent in Singapore and Brunei, to over 9 percent in Indonesia. Clearly, testing in the region is inadequate and the scale of the crisis is much larger than the more than 30,000 confirmed cases as of April 21.

A handful of governments were extremely proactive, quickly put in place robust testing regimens, did contact tracing, and imposed strict quarantines at the short-term expense of their economies. Other governments were in complete denial, downplaying the crisis for fear of negative economic repercussions.

A successful response has nothing to do with regime type. Some democracies (Taiwan (China), South Korea, and New Zealand) have had fantastic responses, while others, the Philippines and Indonesia, have a bit floundered. Likewise, some autocracies have done a good job, while others have been at the forefront of virus denial. A government’s success in flattening the curve is the result of leadership and competent government administration, regardless of regime type.

No government should be blamed for a pandemic, but they should be scrutinized for how they respond. There are four interrelated criteria to understand why some states have succeeded, while other states look like they are in for a very rough ride — with devastating economic impacts — until a COVID-19 vaccine is developed and mass produced.

1. Leadership

While economically painful in the short run, governments that were decisive, implemented public health screening and contact tracing measures, were willing to bite the bullet and shut down both international and domestic travel, and shutter non-essential businesses fared well. We saw this most clearly in Vietnam and Singapore during its first wave of the pandemic.

Leaders who made decisions based on medical and scientific evidence — deferring to their public health and medical officials — have come out on top. Leaders who have made their public health decisions based on short-term economic and political calculations have not been able to get ahead of the situation. Indeed, they lost very valuable time, and in a pandemic, with exponential growth, every day matters.

Governments that used COVID-19 to accumulate power, attack the media, and silence critics, have fared poorly. Using emergency powers in such ways only serves to build mistrust.

Effectively responding to a pandemic requires a whole-of-government approach. Governments that had a holistic strategy to deal with food supply and public health, create a broad-based stimulus package, and mitigate the economic slowdown were able to win public trust and compliance. This requires effective inter-ministerial coordination.

2. Government Transparency

Governments that communicated with their publics in a transparent manner tended to quickly win the confidence of their publics. The governments that admitted the problem, communicated the risks, outlined effective mitigation efforts, and spoke with one voice, have fared much better than governments that have multiple speakers or leaders who downplayed the threat, have publicly reversed their policies, spewed scientific nonsense, looked for scapegoats, and repeated conspiracy theories. Greater trust led to much greater social compliance when it came to wearing face masks, social distancing, and sheltering in place.

Vietnam, in particular deserves plaudits, and not just for their TikTok dances and catchy handwashing song. They have come a long way: When SARS hit in 2003, after a disastrous initial response, the government has become a model of transparency and effective communication. In thee present crisis, Vietnam started on the right foot.

|

| Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc, left, and his staff prepare documents ahead of the Special ASEAN summit on COVID-19 in Hanoi, Vietnam Tuesday, April 14, 2020. Credit: AP Photo/Hau Dinh |

Indonesia might be a democracy with a fairly free press, but its president downplayed the threat, then publicly admitted that he downplayed the threat while peddling nonsense about herbal remedies. The minister of health attributed the early lack of cases to prayer.

Thai public health leaders have looked to foreign scapegoats and made outrageous assertions, while the prime minister seemingly contradicts himself at every turn. In the Philippines, the people want facts not the tiresome bluster of Duterte, who has threatened to shoot people who violate quarantine.

3. Legitimacy

Public trust is tied to another issue: government legitimacy. Governments that had low levels of legitimacy, which leads to corresponding low levels of public trust, fared more poorly. Legitimacy leads to greater public trust, and thereby to greater social compliance when it came to coping with economic losses, social distancing, and sheltering in place.

The Malaysian government came to power in February following a political coup d’état that established a pan-Malay government, overturning the popular election results of 2018. The government has heeded their advice and imposed a very strict stay-in-place order. It is the first government in the region to flatten the curve.

Indonesia, the president admitted to covering up the early spread of the virus for fear that it would have a negative impact on the economy. He encouraged tourism as other countries were locking down. He did not put in place social distancing measures until the virus was running rampant.

The Philippines now has third highest number of COVID-19 cases in Southeast Asia, with the second highest case fatality rate. Duterte’s response has been inconsistent and ham-fisted. The higher rates of poverty in the Philippines will exacerbate the pandemic’s spread. With such a large percentage of the population living at the poverty line, the ability of large swaths of the population to shelter in place and not work is minimal.

In the Philippines, Cambodia, and Thailand, the governments have adopted emergency powers, while Widodo toyed with the idea in Indonesia.

The Vietnamese government has far less money at its disposal to enact a broad-based stimulus, or even immediate cash payouts to businesses and affected citizens. But people have accepted that and are willing to incur short-term pain because the government is deemed legitimate and competent.

4. Planning and Preparedness

The COVID-19 pandemic was not a “black swan” event (low probability, but high impact). It was a “pink flamingo” event, glaringly obvious, but something that political leaders turned away from and ignored. Every few years since SARS in 2003, epidemiologists and virologists have been warning about a major pandemic that is fairly lethal, quickly transmissible, and that can leap from animals to humans. This was both knowable and known.

Governments that were prepared, including having a pandemic response plan incorporating lessons learned from other pandemics such as SARS, H1N1, the Swine Flu, MERS, etc., have fared better. Those that stockpiled PPE and maintained the physical infrastructure to do rapid and mass testing and contact tracing, as well as having made sufficient investments in medical professions, hospitals, and local-level clinics, have fared better. Governments, such as Singapore, which have adopted technology to enforce quarantines and conduct contact tracing, have fared better.

Governments who starved their public health system of resources have fared poorly. It is worth taking a look at the Global Health Security Index as a baseline reference point.

And here I want to make a clear distinction between public health and the medical sector. Vietnam’s medical sector is really quite rudimentary. Yet they have extremely good public health because it is cost effective. Prevention is pennies on the dollars of the cure. Testing, contact tracing, thermometers are really cheap compared to ICUs with ventilators. Vietnam has conducted well over 200,000 tests, or 2.1 tests per 1,000 people. In contrast, as of April 19, Indonesia had conducted under 50,000 tests, only 0.15 per 1,000.

Thailand has fared well so far, in spite of its political leaders, because it has such a good public health system, world class hospitals, and nationwide network of provincial and district hospitals. The Global Health Security Index makes clear that Thailand had the best medical infrastructure to cope with the crisis in the region.

The Philippines has starved its domestic public health system. Despite having very good nursing schools and medical schools, many of its medical professionals work overseas.

Singapore’s initial first-world response to COVID-19 was quickly undermined by a second wave, the result of the compact and poor living conditions of some 300,000 migrant workers, which allows Singapore to have its first world infrastructure and lifestyle.

It is a reminder that viruses are not bound by class, wealth, ethnicity, or status. More importantly, it is a reminder that public health is determined by the least common denominator. If the poorest and most marginalized within a society are not protected then no one is. That is a lesson that all governments need to take to heart.

|

| Chairman of the government office Mai Tien Dung attends the Special ASEAN summit on COVID-19 in Hanoi, Vietnam Tuesday, April 14, 2020. Credit: AP Photo/Hau Dinh |

The diplomat also reported on Vietnam’s COVID-19 Response Success that as the pandemic escalated in early March, the US-ASEAN Summit and the 36th ASEAN Summit were postponed, but Vietnam could still find venues to export its domestic success. On March 31, Vietnam’s Deputy Foreign Minister Nguyen Quoc Dung chaired the first teleconference of the ASEAN Coordinating Council Working Group on Public Health Emergencies. The meeting was followed by a teleconference between senior officials of ASEAN and the United States, attended by U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs David Stilwell, on April 1. Both meetings aimed to promote cooperation within the ASEAN Community and between ASEAN and the United States to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic by sharing information about the situation and implementation of measures taken in each country, while affirming the commitment to strengthen cooperation. Following these meetings, Vietnam chaired the 25th ACC Meeting on April 9 and the Special ASEAN Plus Three (APT) Summit on April 14 in which ASEAN members and their dialogue partners China, Japan, and South Korea agreed in principle to set up a joint fund to combat the pandemic.

Bilaterally, Vietnam has donated test kits and masks to many countries. Among them, Cambodia and Laos are its close friends, and the United States, United Kingdom, and Spain are its comprehensive and strategic partners. In supporting others, Vietnam has demonstrated its commitment to traditional relations and strengthened relationships with important partners.

Vietnam’s model is an example for countries and territories with limited resources and/or at early stages of fighting COVID-19 with a low number of cases.

| The Asian Development Bank (ADB) President offers support for Vietnam's Covid-19 response The Asian Development Bank (ADB) on 24 March expresses its willingness in an official letter to offer Viet Nam with timely and flexible support for ... |

| Singapore remains top city for East Asian expats Singapore has been ranked the most liveable city for expatriates from other Asian markets for the 15th year running. |

| Vietnam, Kazakhstan to optimize advantages offered by VN-EAEU FTA Vietnam and Kazakhstan are seeking opportunities and ways to optimize the advantages offered by the Vietnam-Eurasian Economic Union Free Trade Agreement (VN-EAEU FTA). |

Recommended

World

World

Pakistan NCRC report explores emerging child rights issues

World

World

"India has right to defend herself against terror," says German Foreign Minister, endorses Op Sindoor

World

World

‘We stand with India’: Japan, UAE back New Delhi over its global outreach against terror

World

World

'Action Was Entirely Justifiable': Former US NSA John Bolton Backs India's Right After Pahalgam Attack

World

World

US, China Conclude Trade Talks with Positive Outcome

World

World

Nifty, Sensex jumped more than 2% in opening as India-Pakistan tensions ease

World

World

Easing of US-China Tariffs: Markets React Positively, Experts Remain Cautious

World

World