Oxford-developed vaccine appears to shield monkey from coronavirus infection

|

| A rhesus macaque monkey in Hong Kong on April 30, 2011. Ed Jones/AFP via Getty Images. |

Six monkeys given a vaccine developed by the University of Oxford are said to be coronavirus-free 28 days after sustained exposure to the virus.

The result is a promising early sign for the vaccine, which is also undergoing human trials. A working human version, however, remains months away even in the best-case scenario.

The monkey experiment was carried out in late March by government scientists at the Rocky Mountain Laboratory in Hamilton, Montana, The New York Times reported earlier this week.

The vaccine given to the rhesus macaques is called hAdOx1 nCoV-19. Human trials began Thursday and are expected to be finished in September. The process of developing a vaccine is long, and even having a usable product by September would be unusually fast, according to Business Insider.

While Time reported that the vaccine is now set to undergo human trials, with tests scheduled for more than 6,000 people by the end of next month. If the trial proves safe and effective, the scientists are optimistic that with emergency approval from regulators, the first few million doses could be available by September, the outlet said.

The British university has had a head start in trying to develop a coronavirus vaccine — the university’s Jenner Institute ran trials on an earlier strain of the virus last year which proved harmless to humans.

Another research company, Chinese-based SinoVac, is also making progress, however. The company said its tests on rhesus macaques also showed promise — and the company has recently started a clinical trial with 144 patients, New York Post ctied.

Still queries around experimental coronavirus vaccination

on mokeys

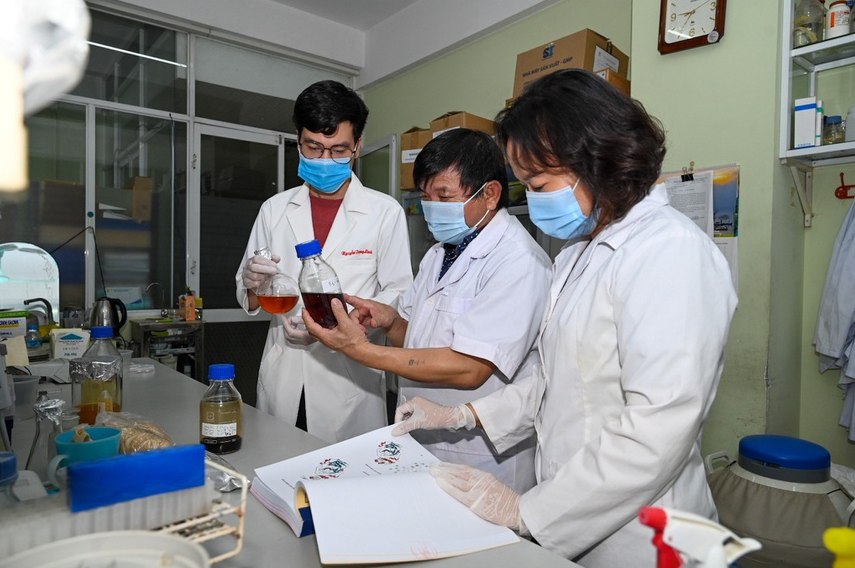

|

| A person works in a lab at Oxford University on a coronavirus vaccine. |

ScienceMag cited Douglas Reed of the University of Pittsburgh, who is developing and testing COVID-19 vaccines in monkey studies, saying that the number of animals was too small to yield statistically significant results. His team also has a manuscript in preparation that raises concerns about the way the Sinovac team grew the stock of novel coronavirus used to challenge the animals: It may have caused changes that make it less reflective of the ones that infect humans.

Another concern is that monkeys do not develop the most severe symptoms that SARS-CoV-2 causes in humans. The Sinovac researchers acknowledge in the paper that “It’s still too early to define the best animal model for studying SARS-CoV-2,” but noted that unvaccinated rhesus macaques given the virus “mimic COVID-19-like symptoms.”

The study also addressed worries that partial protection could be dangerous. Earlier animal experiments with vaccines against the related coronaviruses that cause severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome had found that low antibody levels could lead to aberrant immune responses when an animal was given the pathogens, enhancing the infection and causing pathology in their lungs. But the Sinovac team did not find any evidence of lung damage in vaccinated animals who produced relatively low levels of antibodies, which “lessens the concern about vaccine enhancement,” Reed says. “More work needs to be done though,” the outlet cited.

SARS-CoV-2 seems to accumulate mutations slowly; even so, variants might pose a challenge for a vaccine. In test tube experiments, the Sinovac researchers mixed antibodies taken from monkeys, rats, and mice given their vaccine with strains of the virus isolated from COVID-19 patients in China, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, and the United Kingdom. The antibodies potently “neutralized” all the strains, which are “widely scattered on the phylogenic tree,” the researchers noted.

In topics

Recommended

World

World

Pakistan NCRC report explores emerging child rights issues

World

World

"India has right to defend herself against terror," says German Foreign Minister, endorses Op Sindoor

World

World

‘We stand with India’: Japan, UAE back New Delhi over its global outreach against terror

World

World

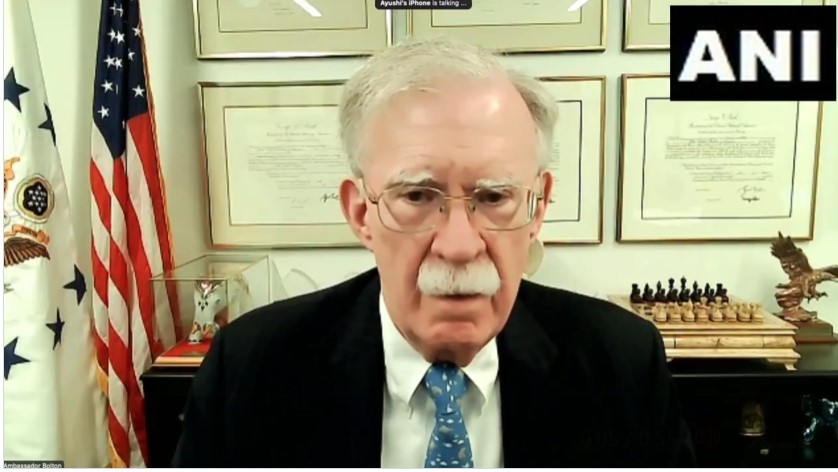

'Action Was Entirely Justifiable': Former US NSA John Bolton Backs India's Right After Pahalgam Attack

Popular article

World

World

US, China Conclude Trade Talks with Positive Outcome

World

World

Nifty, Sensex jumped more than 2% in opening as India-Pakistan tensions ease

World

World

Easing of US-China Tariffs: Markets React Positively, Experts Remain Cautious

World

World