Florida Faces Worst Outbreak Yet with Delta Variant

As the highly contagious Delta variant of the virus rips through the unvaccinated population in the United States, Florida is heading toward its worst outbreak since the start of the pandemic.

The state is still about one month away from its peak, according to an epidemiologist who has been tracking the virus’s reach there.

“Short term and long term, the cases are going to explode,” Edwin Michael, a professor of epidemiology at the University of South Florida, in Tampa, said in an interview on Monday. “We are predicting that the cases will be peaking the first week of September.”

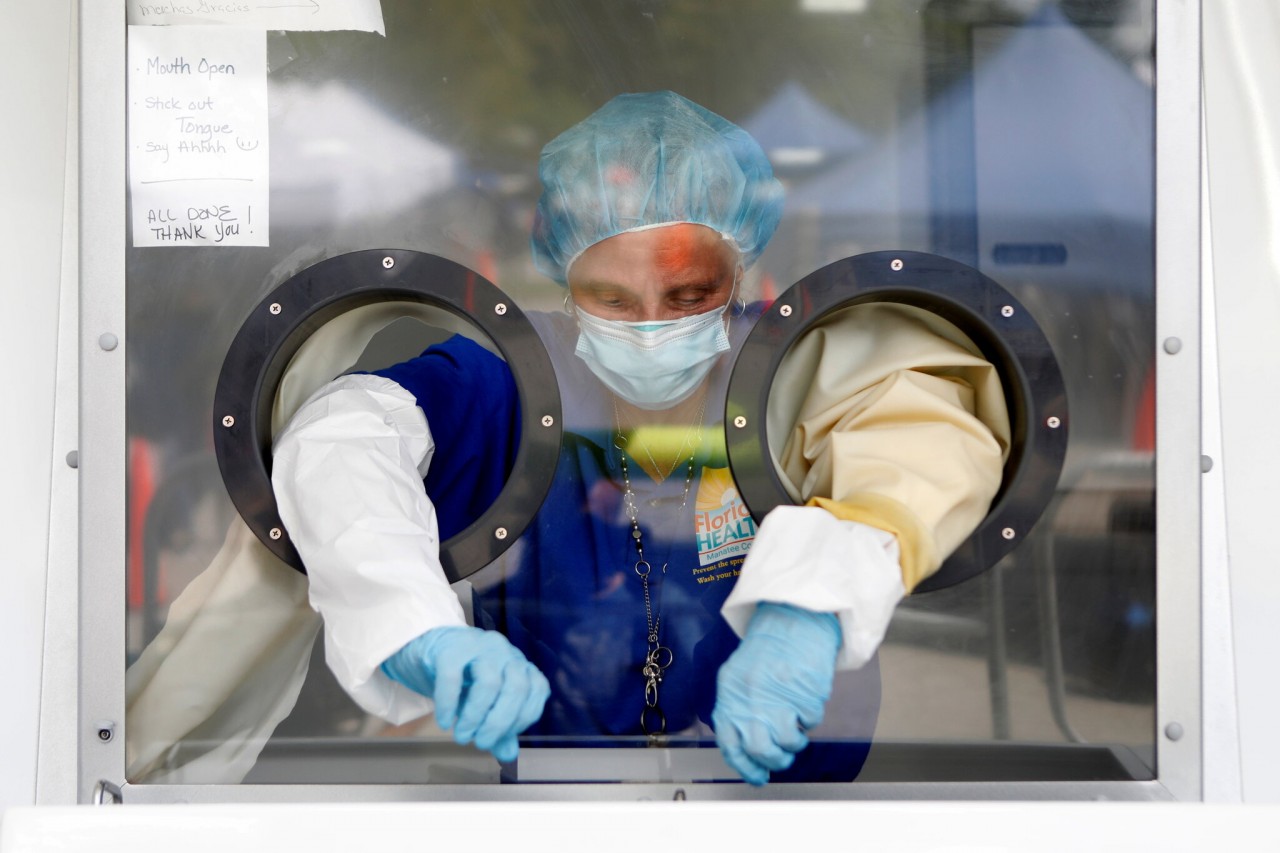

|

| A healthcare worker prepared to conduct Covid-19 tests at a mobile testing site in Palmetto, Fla., on Monday. Photo: Reuters |

Dr. Michael models predictions of the coronavirus statewide and in each Florida county, and his team’s work is used by officials and hospitals to support plans and responses to the pandemic.

“Our simulations show that if we don’t slow the hospitalizations, if we don’t prevent the wave of coming infections, we might exceed Florida’s bed capacity in early September,” he said.

In the last week, hospitals around the state are reporting an average of 1,525 adult hospitalizations and 35 pediatric hospitalizations a day, and cases have risen to levels not seen since January.

“We need a two-pronged approach,” Dr. Michael said. “Get as many people vaccinated as possible, especially the pediatric population. But to prevent the coming waves, we need to couple it with social-distancing measures and face-mask mandates.”

He lamented that it was too late for vaccinations — which take five weeks from the first dose to full protection — to prevent the coming peak, and he insisted that the only way to have a quick impact on the Labor Day wave was to have the extra protective measures.

“The next four weeks are going to be so crucial,” he said. “Schools and universities are reopening in Florida. This is going to be a dangerous period coming.”

The pace of vaccination has plunged since April. That, coupled with a collapse in people taking precautions, allowed Delta to flourish. “Barely 5 percent are practicing social measures,” he said.

On Friday, Mr. DeSantis barred school districts from requiring students to wear masks when classes begin next week, leaving it to parents to decide whether their children wear masks in school.

“In Florida, there will be no lockdowns,” Mr. DeSantis said. “There will be no school closures. There will be no restrictions and no mandates.”

How does Delta variant make the situation in Florida so uncontrollable?

The knowns

Even high levels of vaccination in local regions are not enough to prevent the spread of the Delta variant.

According to Atlantic, although the randomized controlled trials on vaccine efficacy indicated that the vaccines conferred substantial protection from symptomatic infection—with efficacies touted at about 95 percent for the mRNA vaccines—their real-world performance is almost certainly lower, though to what extent is not exactly clear.

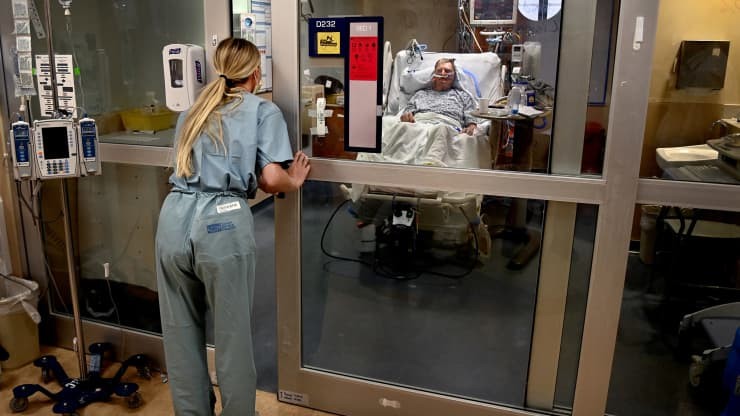

|

| A nurse checks in on a Covid-19 patient in the Covid ward at Tampa General Hospital in Tampa, Florida. Photo: Getty Images |

At the same time, more and more evidence suggests that some people with breakthrough infections can transmit the virus. Combine those two facts with Delta’s extremely high transmissibility, and we’ve found ourselves in a world where even well-vaccinated communities can see quick growth in cases. Back in the pre-variant days of the pandemic, 70 percent vaccination was seen as a rough goal to achieving herd immunity, the point at which viral growth could no longer be sustained in a community. Yet San Francisco, which has 70 percent of its population vaccinated, has nonetheless seen a similar case surge to the one in Maricopa County, home to Phoenix, Arizona, where only 43 percent of residents are vaccinated.

Although, statistically, counties and states with higher vaccination rates have lower case counts and hospitalization rates, they have still become areas with high levels of community spread.

There are probably different transmission dynamics within these cities. Young, unvaccinated people are likely responsible for a good deal of transmission. There are, after all, still 50 million kids under 12 who are not eligible for the vaccines. But it’s also likely that older, vaccinated people are responsible for some spread as the amount of virus increases in the community.

In a number of places, this has not caused major increases in hospitalizations, but that’s not universally true. Perhaps the most startling example is The Villages, in Florida. Centered on a retirement community, this metropolitan area has close to 90 percent of its over-65 population immunized, yet it has seen a surge of cases and hospitalizations.

There is still a lot of randomness to where the worst outbreaks occur.

Although, again, statistically, places where more people are vaccinated are faring better than places where fewer people are vaccinated, there is enormous variability lurking in the numbers. Some of it may be explainable by policy decisions and political allegiances. But some of it is also just luck.

Back in the spring, when the variant we were most worried about was called Alpha, Michigan and almost Michigan alone got absolutely torched, matching its peak for hospitalizations from the winter. This didn’t happen anywhere else, though some epidemiologists expected it to, based on the experience of European countries. Alpha just kind of went away, and it seemed like the U.S. might be in the clear.

Enter Delta. In this surge, a piece of Missouri began to take off before the rest of the country. Would it be like Michigan? As we all now know, the answer was no. The southeastern United States is now experiencing huge outbreaks as many states come close to matching or surpassing their pandemic peaks in cases and hospitalizations.

The health-care system in north Florida is under pressure that few places have seen at any time during the entire pandemic. Why there? Why not somewhere else with similar vaccination rates and political opposition to viral countermeasures? No one knows with total certainty, and we’re unlikely to ever find out.

Vaccinated people can be infected with and transmit the virus.

Breakthrough infections for vaccinated people were always going to happen. No vaccine provides perfect immunity, and the immune system is strange and somewhat unpredictable.

But there was some logic to the hope that maybe these infections wouldn’t transmit the virus forward. Because the large majority of vaccinated people have mild symptoms, the thinking went, perhaps they would have lower viral loads, and therefore be less likely to spread the virus.

How well the vaccines protect against any infection (not just symptomatic infection, hospitalizations, or death) is a hotly disputed topic. A variety of data suggest that vaccination does help prevent exposures to the virus from becoming infections, and that, obviously, helps slow the spread of an outbreak.

|

| Photo: WebMD |

But it’s also become clear that vaccinated people who do get infected can spread the virus. The most recent piece of evidence came when American scientists were able to culture virus from samples taken from vaccinated people who’d gotten infected. Those same people showed similar viral loads to unvaccinated people. And yes, even those with asymptomatic infections.

Although that’s bad news, there is some good news too: Breakthrough infections appear to be significantly shorter than infections in the unvaccinated. That would reduce the amount of time that people with breakthrough infections could spread the virus.

There will undoubtedly be many more studies along these lines, and the papers cited above are preprints, meaning that they have not yet been peer-reviewed. But the data, including unpublished studies cited by public-health officials, are pointing in the same direction: Breakthrough infections are happening. And when they do, those people can spread the virus.

The unknowns

How well do the vaccines work to prevent infection?

As noted, all available data show that the vaccines remain remarkably effective at reducing the risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19. But past that very important outcome, the data are much murkier.

So the effectiveness of the vaccines is a matter of perspective. What people might refer to as vaccine effectiveness can have different meanings, and therefore the nature of their data and calculations can vary. If we want to talk about vaccine effectiveness precisely, we need to specify effectiveness against an outcome (infection, symptomatic disease, hospitalization, death). We also need to define the temporal parameters: across how long of a time period? When were the vaccines administered? We need to break out the different vaccines. We need to have a rough understanding of the variants in circulation when a given study was done. And finally, we need to specify which population is under discussion—young, old, immunocompromised, health-care workers, etc.

Sure, all these factors can be rolled up, and had to be rolled up during the vaccine approval process, into a single number to determine vaccine efficacy. That number came out to 95 percent in the original trials for the mRNA vaccines.

For the time being, it seems prudent to assume that it’s possible that one or more of the vaccines will be found to have substantially lower real-world performance in preventing Delta infection and/or symptomatic disease.

|

| The emergence of variants of concern in late 2020 marked a shift in the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo: Shutterstock |

Why have so many more people been hospitalized in the United States than in the United Kingdom?

Florida had a larger share of its population vaccinated at the start of the American Delta wave than the U.K. did when it saw the variant’s exponential rise. Yet, in Florida, the state now has nearly double the number of COVID-19 patients in hospitals than it has ever had during the pandemic.

It will take a long time to tease out the different factors between the U.S. and the U.K. Obviously, for example, the United States is a much larger country with distinct types of urban structures.

But there are several other immediate pathways for thinking about why things are playing out so unlike in the U.S. The U.K.’s vaccination strategy was substantially different from the American one, despite the overall similarity of vaccination rates. It could also be that American unvaccinated people were spread more unevenly through the country than the unvaccinated in the British context, with different epidemiological effects.

Looking at Florida, though, one thing stands out. For reasons few epidemiologists could understand, the state had not been hit as hard as neighboring places with similar populations and politics. Look at almost any metric before the Delta wave, and Florida fared pretty well relative to New York, California, or Illinois. Not until the current Delta wave has Florida experienced a surge comparable to those seen in other big states.

The U.K., by contrast, was hit with two massive COVID-19 waves in which the death rate was nearly twice what it was in the U.S. That suggests that a much greater percentage of the U.K. contracted the virus, giving them some natural immunity. The virus may have run out of bodies to attack.

Perhaps, in Florida, the state’s good fortune in previous waves—along with the political opposition to societal countermeasures—could be one of the factors driving this gigantic increase in COVID-19.

| HCMC Lockdown: Indian Restaurant Owner Donates Hundreds of Meals to Struggling Residents Closing the restaurant business because of the pandemic lockdown, Robin Deepu has used his kitchen to cook free meals for people in Ho Chi Minh ... |

| Russia Reports Record-High Covid-19 Deaths to Date Daily Covid-19 deaths in Russia hit a new record of 819 on August 14 as a third wave of infections persists despite efforts from authorities ... |

| Overseas Vietnamese Joins Hand to Fight Covid-19 A webinar was held on August 12, focusing on "Overseas experts working with Ho Chi Minh City to fight the pandemic." Experts from across the ... |

Recommended

World

World

US, China Conclude Trade Talks with Positive Outcome

World

World

Nifty, Sensex jumped more than 2% in opening as India-Pakistan tensions ease

World

World

Easing of US-China Tariffs: Markets React Positively, Experts Remain Cautious

World

World

India strikes back at terrorists with Operation Sindoor

Popular article

World

World

India sending Holy Relics of Lord Buddha to Vietnam a special gesture, has generated tremendous spiritual faith: Kiren Rijiju

World

World

Why the India-US Sonobuoy Co-Production Agreement Matters

World

World

Vietnam’s 50-year Reunification Celebration Garners Argentine Press’s Attention

World

World